Marilyn is featured in DIVA, a new exhibition at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum (the V&A), celebrating the power and creativity of iconic performers, exploring and redefining the role of ‘diva’ and how this has been subverted or embraced over time across opera, stage, popular music, and film. (Pre-booking is essential for this exhibition, which runs through to April 2024.)

Sam Shaw’s iconic 1954 photo of Marilyn, captured during filming of her ‘subway scene’ for The Seven Year Itch, appears in a ceiling mural pointing visitors towards a heavenly galaxy of divas old and new.

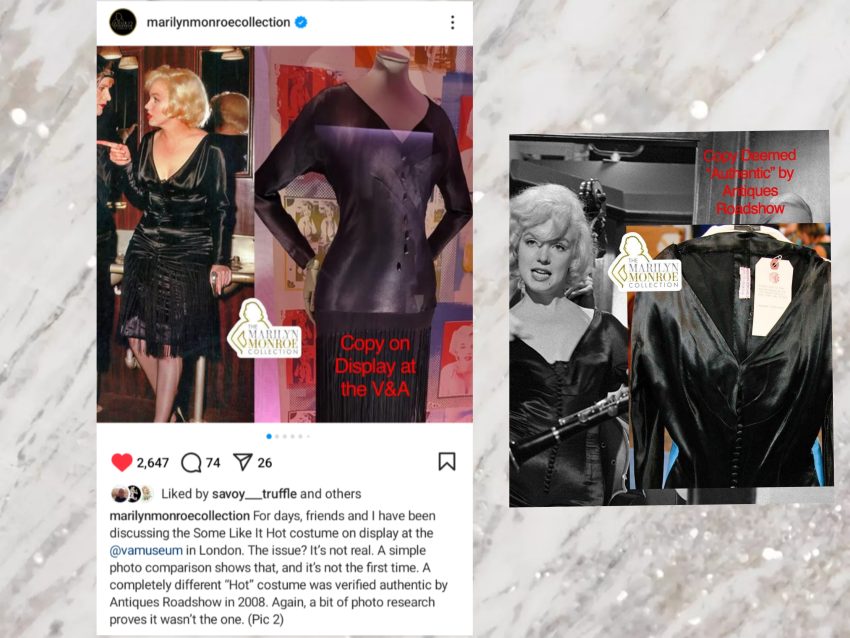

A black satin fringed dress allegedly made by Hollywood designer Orry Kelly for Marilyn’s ‘Running Wild‘ number in Some Like it Hot (1959) was acquired by the British Film Institute in the 1980s as part of their costume collection. It was displayed at the Museum of the Moving Image from 1988 until the venue’s closure eleven years later.

This collection, including the dress, was transferred to the V&A in 2015. (The semi-transparent white dress she wore for the ‘I Wanna Be Loved by You’ number was recently featured in the similarly themed Goddess exhibition at ACMI in Melbourne, Australia.)

However, experts including collector Scott Fortner and historian April VeVea have made compelling arguments that this is not in fact Marilyn’s costume, citing several major differences. Some fans who visited the exhibition were also unconvinced, and have contacted the museum to share their concerns.

Despite this negative feedback, the costume remains on display as part of this exhibition. An item description on the V&A Collections website notes that “sometimes costumes are modified, and often more than one version of a look is made for a performer.”

The dress is displayed alongside a contrasting photo, which seems to evoke the private tumult that often lurked behind Marilyn’s dazzling glamour. It’s a cropped version of a photo taken by Arnold Newman at a party in 1962, which originally showed Marilyn deep in conversation with the poet Carl Sandburg.

Additionally, a 1967 screenprint by Andy Warhol signifies Marilyn’s enduring cultural impact. And as Jessica Wall writes for The Upcoming, “there is also a script from Monroe’s breakout hit, Niagara, in which she has annotated, in precise capitals written in cerise ink, the name of her character in the film with the name of the character she would play for the rest of her life.”

‘Diva’ was a term first used in 16th century Italy to describe the leading ladies of opera. This continued into the 19th century, when the Swedish-born Jenny Lind became internationally renowned. In 1946, as Norma Jeane Dougherty embarked on her acting career, she briefly considered using the stage name ‘Carole Lind’ – combining Lind’s last name with Carole Lombard’s first name – before choosing Marilyn Monroe instead.

The gown worn by Bette Davis in All About Eve (the Oscar-winning satire in which Marilyn played a supporting role) is also featured in the exhibition.

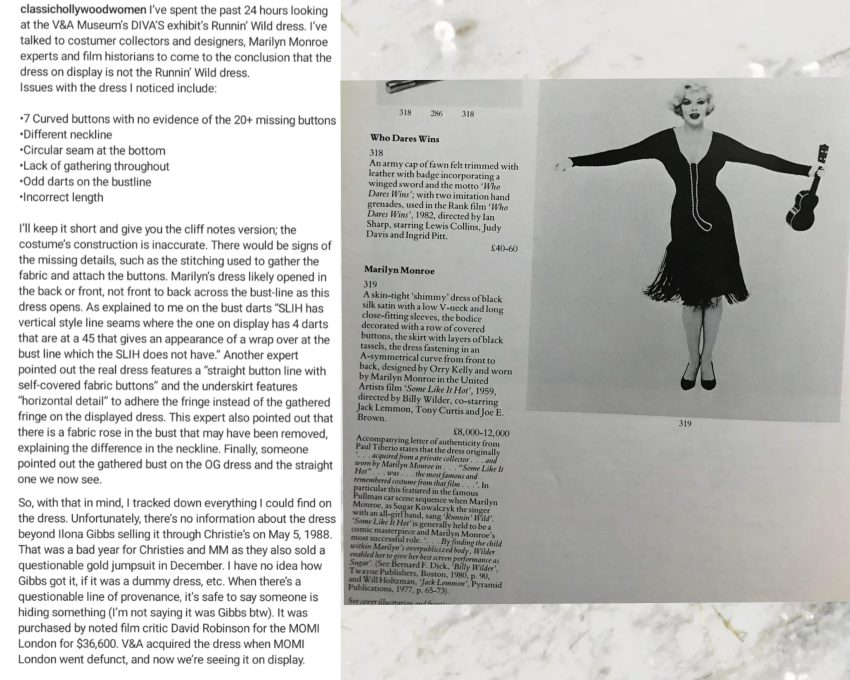

Sarah Bernhardt was a ‘diva’ of the theatre, and is often cited as the first modern celebrity. In a 1951 profile for LIFE magazine, Marilyn was described as a ‘busty Bernhardt.’ Her predecessor is also mentioned in an amusing scene from The Seven Year Itch, where Marilyn’s character (known only as ‘The Girl’) discusses her role in a toothpaste commercial with her neighbour, Richard Sherman (Tom Ewell.)

“THE GIRL: People don’t realise, but when l show my teeth on TV, l appear before more people than Sarah Bernhardt ever did. Something to think about.

SHERMAN: lt certainly is.

THE GIRL: I wish l were old enough to have seen her. Was she magnificent?

SHERMAN: l wouldn’t know. l’m not that old myself.

THE GIRL: l guess you’re not really.”

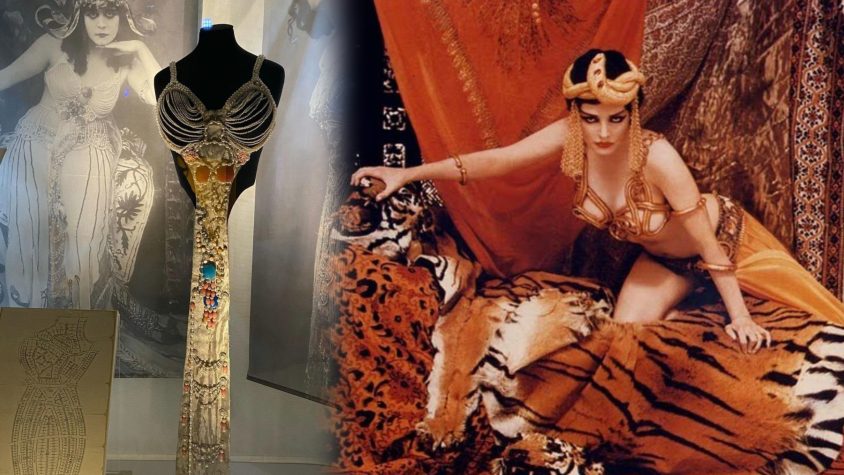

In 1958, Marilyn impersonated silent movie diva Theda Bara as part of her ‘Fabled Enchantresses‘ layout for LIFE magazine, photographed by Richard Avedon. An original costume piece worn by Bara is featured here.

Josephine Baker epitomised the jazz-age diva. Marilyn attended her cabaret show at the Hollywood Hartford Theatre with Yves Montand in 1960.

The opera singer Maria Callas was a fellow performer at Madison Square Garden on President Kennedy’s 45th birthday, and she was introduced to Marilyn backstage.

A diva in his own right, Elton John paid homage to Marilyn with his 1973 single, ‘Candle in the Wind.’

In 1991, Madonna arrived at the Oscars in a Bob Mackie gown inspired by Marilyn’s dazzling look at the premiere of How to Marry a Millionaire (1953.) The pop superstar also wore the dress for a Monroe-inspired cover story for Vanity Fair.

The beaded ‘nude dress’ that Marilyn wore to sing ‘Happy Birthday Mr. President’ was a direct inspiration for pop star turned style mogul Rihanna’s even more daring look at the CFDA Fashion Awards in 2014. Designer Adam Selman followed Marilyn’s lead, encrusting the gown with Swarovski diamonds.

The exhibition is featured in Hello magazine’s UK edition (#1797, dated July 10th):

“‘How do you get performers like Beyonce and Lady Gaga?’ says V&A curator Kate Bailey. ‘You can’t imagine Gaga without Madonna, or Madonna without Marilyn.’

Some Like It Hot star Marilyn is represented in the exhibition by a tasselled dress she wore in the film Her inclusion, says Kate, ‘helps unpack the Hollywood studio system and the relationship between public and private.’

She might have been stereotyped as a vulnerable ‘dumb blonde’, but ‘she was trying to push boundaries in her acting,’ Kate says. “I read the newspaper articles about her, and the way she was treated, and she still manage to drag herself up and out.'”

And finally, Marilyn is also featured in DIVA, a book accompanying this exhibition – and here’s an excerpt…

“With the artist’s increasing boldness and drive to rock the status quo came an increasingly negative depiction of the diva, as many female performers were forced to work within the power structures of the studio system. This negative attitude and control gathered momentum later in the 20th century and endemic misogyny has taken generations to unravel, finally given traction and attention with the #metoo movement.

One of those who had been rocking the status quo of male-dominated Hollywood since the 1930s was Mae West (1893 – 1980). In words from her screenplay for I’m No Angel (1933), which reflect her own rebellious spirit, she reassured her followers that ‘When I’m good, I’m very good, but when I’m bad, I’m better’. This mantra gave a voice to future generations prepared to take on the spirit of non-conformity and disruption. Some two decades later Marilyn Monroe (1926 – 62) echoed this sentiment as an artist striving for creative freedom and perfection: ‘I guess people think that why I’m late is some kind of arrogance and I think it is the opposite of arrogance…. The main thing is, I do want to be prepared when I get there to give a good performance to the best of my ability.’

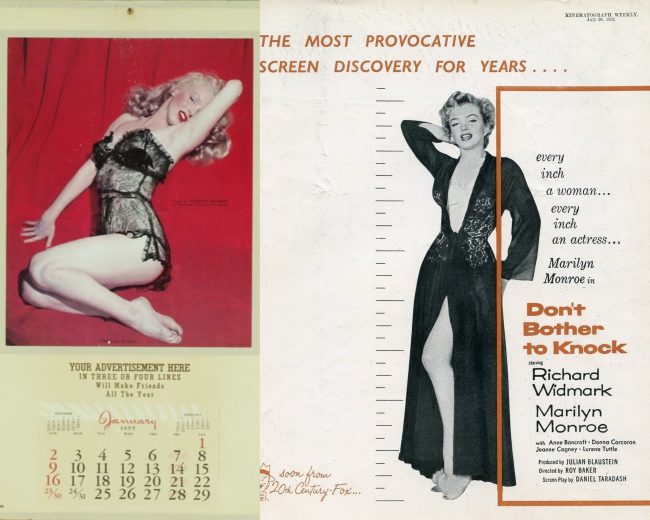

These strong-minded statements about their artistic struggles contributed to perceptions of the diva in the public imagination, often through the lens of a media that would revel in tracing the rise and fall of the most powerful global artists. Consumers were fascinated by their strong personalities and the tension between their public and private lives. For the diva, fame, life and art were under constant scrutiny. In 1952 the Daily Mirror exploited the discovery of nude photos of Monroe months before advertisements promoting her new movie Don’t Bother to Knock used explicitly sexualised images with the strapline ‘every inch a woman, every inch an actress’.

In 1959, at the height of her fame, Monroe, as Sugar ‘Kane’ Kowalczyk in Some Like It Hot sang ‘I Wanna Be Loved By You’ and captivated audiences in a performance that was comic and heartbreaking in equal measure. Wearing a little black shimmy flapper-style dress, Monroe’s emotionally bruised character drinks from her hip flask with her crossdressed co-stars before she entertains and dazzles in a showstopping musical and dance performance, reflecting the duality of the life of the diva on and off stage. Monroe was aware of the power of worshipping fans and how they contributed to her success: in her last interview she allegedly said, ‘if I am a star, the people made me a star. No studio, no person, but the people did’.

Monroe also used her talent, fame and popularity as a positive force for others. She persuaded the owner of the exclusive Mocambo Club in West Hollywood to book her friend Ella Fitzgerald … Monroe, as a fan and friend, demonstrated diva solidarity and power, providing the highly gifted Fitzgerald with a significant career opportunity.

Returning to the world of opera, the birthplace of the diva, Maria Callas is often described as the ultimate diva. Despite widespread fascination with her private life and the intrusive public gaze, Callas remained passionate and vocal about her role as an artist seeking perfection … As creative artists of the 1950s, Callas and Monroe represent a catalyst for the next generation. Their personal frustrations with the containment of their art and creativity chimed with the theories expounded by Betty Friedan in The Feminine Mystique. Published in 1963, the year after Marilyn Monroe’s tragic death, Friedan addressed women’s discontent with a society that limited their opportunities: her treatise challenged women to stop conforming to the conventional picture of femininity, and to enjoy being New Women with identities and lives of their own.” – From ‘Redefining the Diva‘ by Kate Bailey

2 Comments

Comments are closed.