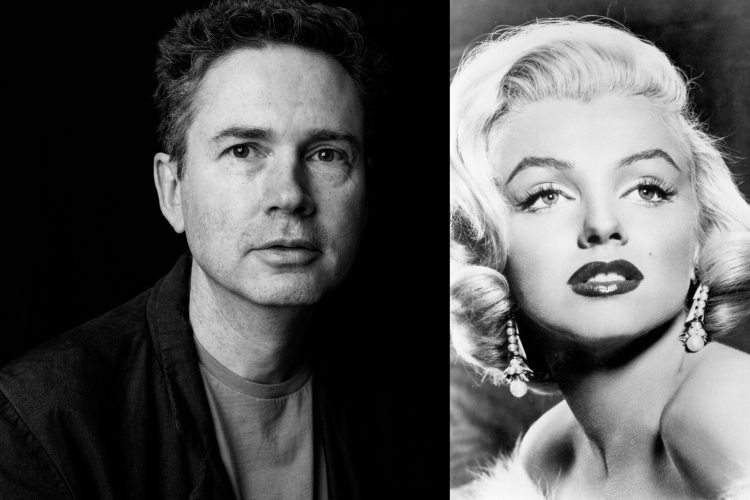

Michael Fitzgerald’s novel, Late, imagines a future for Marilyn beyond 1962, and far from Hollywood. Late is published in Australia by Transit Lounge, and is available elsewhere via Kindle. (The striking cover art is based on a 1953 photo by Frank Powolny.)

“‘So, was it hard to pretend I was dead? Well, my motivation was abundant; it was splendiferous, endless, you might say.’

An American actress, renowned for being late, is living with her two cats in a modernist clifftop apartment in Sydney in the late 1980s.

The recounting of her story is prompted by the arrival of an old typewriter and a book addressed to Zelda Zonk. And by the arrival of a young man called Daniel, who is locked out while house-sitting her neighbour’s apartment.

Together Zelda and Daniel form an unlikely but close bond as they go walking, prepare dinner for Shabbat, traverse Sydney Harbour on a ferry and talk about their lives. Part of their bond is the discovery that they are both orphans. Daniel is also a habitué of the nearby sandstone cliffs where men have mysteriously gone missing.

In Late, Michael Fitzgerald superbly captures the literary spirit and sensibility of an ageing woman and icon who has escaped celebrity. It is a haunting and lyrical novel about art, friendship, and confronting our fears.

‘A big swing that works beautifully. Fitzgerald’s affection and respect for his subject, whom we all know and don’t know at all, results in a voice that rings true: warm, tender, passionate, smart, self-aware and very, very witty.’

C. J. Johnson, President of the Film Critics Circle of Australia

‘Deeply referential, dramatic and allusive, Late balances on a tightrope between present and past lives, public and private roles. A riveting mystery unfolds. In the process the author delivers a meditation on celebrity and a love song to Sydney.’

Catherine Phil MacCarthy, author of Daughters of the House and One Room an Everywhere

Michael has discussed the novel – and Marilyn – in an interview for The Curb.

“What was the foundation of your version of Marilyn?

Michael Fitzgerald: I’ve [worked for] the last couple of decades in the visual arts, editing art magazines, but all along, my secret passion has always been cinema and I realise I’ve never really been able to fully express it. A figure like Marilyn Monroe, even though she’s not explicitly the subject of the book, her alter ego Zelda Zonk is, and she’s always [been] a fascination for me. It’s almost like a secret affection in the same way cinema holds for me. I keep changing my mind about her as a figure in cinema, but also as a person, and why we’re always so intrigued and fascinated by her. As I’ve got older, I think she’s become more and more fascinating.

In my book, she would be about the same age as me, and it’s speculating on if she hadn’t died and where she might be now, perhaps in the late 1980s [when] she would have been in her late 50s. For someone like myself, what really fascinates me about her is that she eloquently expressed the dilemma of being alive and existing, of being alive in the world. That in itself is such a challenge on how to be herself in the world. That’s such a human quality and such a human existential question for so many people. I think she was always trying to be the best version of herself; she was always trying to improve, trying to be perfect, and that’s something that a lot of people can really relate to considering her choice of film roles and that quest for perfection that you can see on screen and in her off-screen life as well.

Let’s talk about that name. What informs the decision process behind using the name Zelda Zonk?

MF: I’ve got quite a large library of books on Marilyn Monroe that I’ve collected over the years. I think it was in Donald Spoto’s Marilyn Monroe: The Biography – which I still consider probably the best and most sympathetic biography –, there was mention of this alter ego character called Zelda Zonk that Marilyn Monroe assumed around the time of her breakup to Joe DiMaggio when she escaped to New York trying to get out of her Fox contract, and she donned a black wig and assumed this name of Zelda Zonk.

For me, it’s the first name that she chose for herself, and I think it’s incredibly revealing about her. I think there’s an incredible wit and sense of humour and self-deprecation in that name. My book has a slight quality that you could tie with Judaism. I believe Zelda is a Hebrew name or has some association [with Judaism]. The fact that she did convert to Judaism in her third and final marriage to Arthur Miller, I thought for a writer of fiction, it turned her into a perfect character name for my novel where the main character who has converted to Judaism is an American actress that has escaped celebrity to move to Sydney in the 1960s. My book is set in the late 1980s, so it takes up her story a couple of decades on.”

UPDATE: Ellie Fisher has reviewed Michael Fitzgerald’s Late for ArtsHub…

“In the decades since Monroe died, many have attempted to ventriloquise her – perhaps most infamously, Joyce Carol Oates, in her 2000 novel, Blonde – with varying levels of success, and fluctuating degrees of ethical consideration. In Late, Fitzgerald sidesteps some of the clichés that surround Monroe through his decision to give her agency in the novel. By choosing to write through the persona of Zelda, he gives voice to a version of Monroe that is both self-reflexive and incredibly camp.

Late benefits from Fitzgerald’s research muscle – which is revealed in his notes at the end of the novel, as well as the frequent, fragmentary footnotes that populate Zelda’s thoughts on the page – and from his choice to treat his subject with the sort of respect she has, historically, not always been accorded. ‘What I have to say is important and personal,’ Zelda tells the reader. ‘Please promise not to start reading until you have the time and space to give it your careful consideration.’

This sense of urgency, as well as the plea for gentle contemplation, is what gifts Zelda with a sense of realism. She is neither Marilyn Monroe nor Norma Jeane Mortenson; she is a composite of both. Like most of the parts Monroe played throughout her career, Zelda is a fabrication in her own right: a persona that is enacted, or a mask that is assumed.”

1 Comment

Comments are closed.