The Los Angeles County Department of Medical Examiner building – or more simply, the Los Angeles morgue – is located on Mission Road in the Boyle Heights district, and as Corina Knoll reports for the New York Times, it’s unlike any other coroner’s office in the world.

“In most places, it is a trade of little glamour. Transporting bodies, performing autopsies — the role of a coroner’s office tends to be dismissed as a macabre necessity.

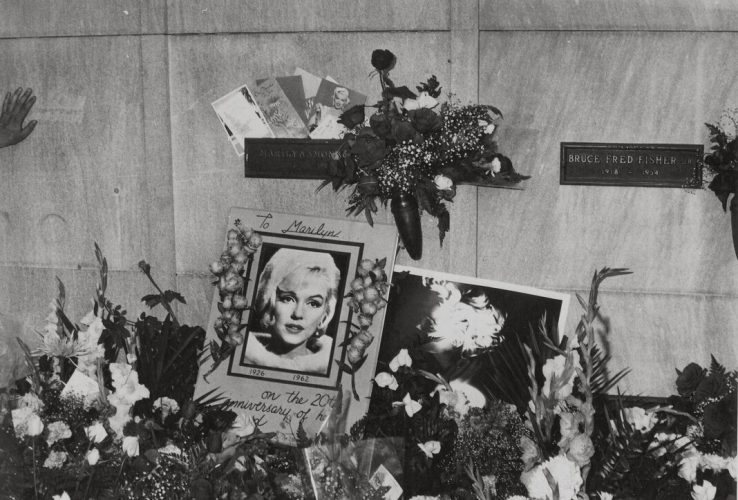

But this is Los Angeles, where the list of those who have died unexpectedly is iconic: Marilyn Monroe. The Notorious B.I.G. Whitney Houston. Michael Jackson.

In late October, it was the actor Matthew Perry … It is the latest celebrity mystery for the office often referred to as ‘the coroner to the stars’ but formally called the County of Los Angeles Department of Medical Examiner. Its workload and unique terrain are unparallelled, spanning 88 cities across 4,000 square miles in the nation’s most populous county. The office must deal with the same tragic notes as any area — traffic accidents, homicides, drug overdoses, suicides — but also earthquakes, wildfires and riots.And celebrities.

In a region still defined by its Hollywood culture, employees have long been accustomed to satellite trucks parked outside. Now, prying eyes are everywhere, as the proliferation of social media and entertainment sites has only intensified the demand for instant answers and the spotlight on high-profile deaths.

‘You get hammered by the press so violently,’ said Bob Dambacher, a former investigator in the office over decades when Robert F. Kennedy, William Holden, John Belushi and Janis Joplin died in Los Angeles County.

Even before the internet, the coroner’s office held mystique. In 1962, Mr. Dambacher and another investigator went to the west side of Los Angeles to retrieve Marilyn Monroe’s body. When he emerged with the covered actress on a gurney, his photo was snapped, soon to be splashed on newspapers around the world.

‘Oh, my goodness, I was just married, and it was a nightmare with people calling me,’ he recalled. ‘I even got fan letters, believe it or not. People wanting to know who I was. It was crazy.'”

Although Dambacher doesn’t believe there was foul play involved in Marilyn’s fatal overdose, he was previously interviewed for a conspiracy-heavy tome, The Murder of Marilyn Monroe: Case Closed (2016.)

“At the time of Marilyn’s death, Robert Dambacher was a deputy coroner. His partner’s name was Cletus Pace. ‘Cleet and I were dispatched at eight in the morning to go out to Westwood Village Mortuary to pick up her remains,’ Dambacher told Jay Margolis. ‘Westwood had gone to the residence. We brought her body back to the Coroner’s Office in Downtown Los Angeles. In retrospect, she should have come to the Coroner’s Office right in the beginning, right from the residence to the Coroner’s Office, but she didn’t … I think she took a deliberate overdose of drugs. She had enough drugs in her to kill about three of us. You can’t accidentally take that many pills.’

In a photo now licensed by Keystone/Getty Images, a young Bob Dambacher stands in front of the older, bespectacled Cleet Pace as they remove Marilyn Monroe from the Westwood Village Mortuary, a building with window blinds to the left and right. Many people have mistakenly assumed the men were taking the body from Marilyn’s home, but as Dambacher confirmed, ‘I never did go to the residence.'”

In 1992, Robert Slatzer published The Marilyn Files (now widely debunked); another book, Marilyn: The Last Take, suggested that her death was covered up by Twentieth Century-Fox; and the case was featured on an episode of TV’s Hard Copy.

Despite the media hoopla, calls for Marilyn’s untimely demise to be reinvestigated were ultimately dismissed – and the findings of the original 1962 investigation and two subsequent enquiries were fully upheld.

That August, the news of Bob Dambacher’s impending retirement was marked by a career profile in the Los Angeles Times.

“Before he retires, however, there is much work to do, including a possible reopening of one of Dambacher’s most famous cases at the request of the County Board of Supervisors–the apparent suicide of Marilyn Monroe. Because of his experience and his responsibilities as special investigator for the office, Dambacher would play an important role in an investigation into her death. But he said all the rumors that she was killed, possibly by agents of the Kennedy family, are just that–rumors.

As he walks the four floors of the coroner complex, it is clear that Dambacher is known–and cherished–by everyone for his die-hard wit and his encyclopedic knowledge of the office and its history. He peppers his remarks with ‘Hi sweetie!’ and ‘Hey there,’ stopping to chat with nearly everyone.

Thomas Noguchi, the once-infamous chief coroner who left his top post with the department under a cloud of controversy, has fond memories of working with Dambacher for more than 20 years. ‘He’s the best investigator and best friend I ever had,’ said Noguchi, now chief medical examiner at County-USC Medical Center. ‘He is a good person, kind and considerate.’

Dambacher never expected to get into the coroner business. He grew up in the tiny farm town of Standard in Tuolumne County, just east of Sonora, population 100. ‘When I was born,’ he quipped, ‘I increased the population by 1%.’

After serving in the Army, he came to Los Angeles in 1955 to attend the pre-dental school at UCLA and ended up getting a job at a Westside mortuary. He was 23, and he still remembers how his knees shook when he was sent out on his first call, to pick up a dead infant.

‘I was very nervous,’ he recalled. ‘But I soon learned to accept it. Not everyone can stay in this business. God knows, it’s a very difficult profession to be in.’

In June, 1958, Dambacher took a job as a morgue attendant at the coroner’s office. At first, he stayed ‘out of necessity.’

But then he became fascinated with the challenging process of investigating deaths, which he describes as ‘playing doctor to policemen, and policeman to doctors.’

Police are in charge of investigating the scene of a crime, he explained, but it is the medical examiner who must take charge of the body, and look for clues as to how and when the person died, and why.

Dambacher rose from mortuary attendant and autopsy assistant to investigator in 1965, and then worked up the line to chief of investigations, ultimately becoming special investigator to the department head in 1984. In 1988, he took on the added role of press information officer.”