As author Sarah Churchwell wrote in her 2004 book, The Many Lives of MM, Marilyn is often mentioned when a famous woman dies – especially if she happens to be young and blonde. And in 2017, podcaster Karina Longworth devoted an entire season to the ‘Dead Blondes‘ of Hollywood.

Now, as Roxanne Adamiyatt writes for Town & Country magazine, Edie Sedgwick, Grace Kelly and Princess Diana can also be added to the pantheon – not to mention Carolyn Bessette Kennedy, who died aged 33 alongside husband John F. Kennedy Jr. in a 1999 plane crash, and is the subject of Once Upon a Time, a new biography by Elizabeth Beller.

“The Dead Celebrity Industrial Complex is big business—at least $1.6 billion in 2022, according to Forbes‘ tally of the 13 highest-earning late performing artists, including Whitney Houston and Michael Jackson. The blondes from the great beyond, are a particular substratum of this industry, and the public’s, um, undying fascination with them is tied up with widely accepted beauty standards, a certain morbid fascination with misfortune, and something of an X factor.

M.G. Lord, a professor at USC and the author of Forever Barbie, a social history of the world’s most popular plastic blonde, says, ‘When you die young, no one can ridicule your imperfections later on. What endures are the perfected images.’ And so these icons stay fixed in the public consciousness, unperturbed like contemporary sleeping beauties. ‘They evolved beyond reality into a fairy tale.’

The value of this perfection, preserved in celluloid, seems to have increased exponentially in the social media era. ‘We’re at the end of image making,’ says Claire Parker, co-host of the podcast Celebrity Memoir Book Club. Instead of boundary-breaking new photographs, Pinterest, TikTok, and Instagram reward nostalgia.

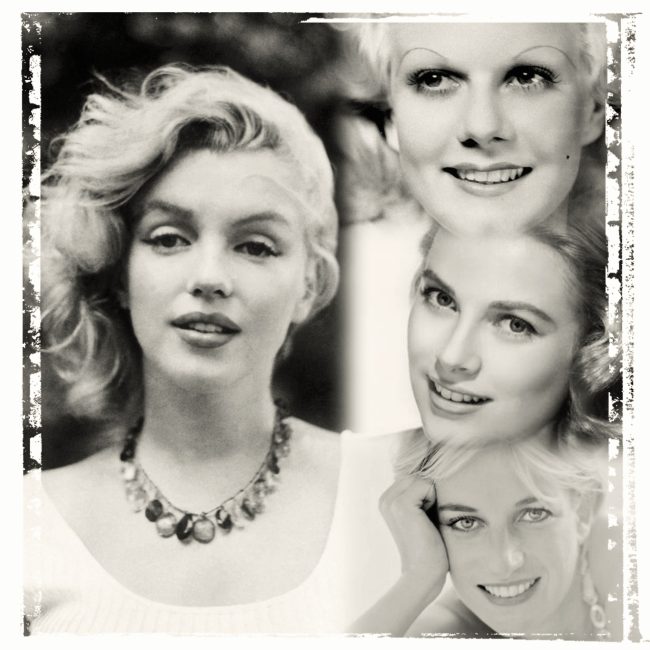

Arguably, the trope of the tragic blonde began with Jean Harlow, who died at 26 in 1937 on the set of Saratoga, just seven years after her breakthrough in Howard Hughes’s Hell’s Angels. Her last film became the highest-grossing one of her brief career. She was followed in the annals of hair-story by Monroe, who died at 36 six decades ago, although you wouldn’t know it from how ubiquitous she remains.

Her estate made $10 million last year from a variety of licensing deals, including an NFT collection and lingerie by Fleur du Mal, according to Forbes … ‘We love a dead woman because she’s the perfect victim,’ Parker says. ‘She can’t be diluted by the trend cycles. You’re always seen as who you were.’ That many of these figures are connected to larger groups—say the Kennedy family or the rulers of Monaco—contributes to their relevance in an age of diluted fame and fractured followings.

When all that endures of a famous person is an idealised image (Monroe singing ‘Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend’ or Diana in her revenge dress), her likeness takes on a life of its own in the public imagination. ‘Much like Barbie, which is an idea that you can own, the commodification of these blondes causes them to re-materialise for a new generation of people and consumers,’ Lord says.

‘The thing with celebrities today is the familiarity,’ Parker says. ‘People feel connected by thinking that they know someone. When a celebrity dies young, there’s not enough for us to know. We aren’t exhausted by them.’ So we keep on liking, pinning, regramming, and blonde-scrolling for more.”