The latest reissue of Eve Arnold’s Marilyn monograph was reviewed by Irish novelist John Banville for The Observer yesterday.

“It is not special pleading on Arnold’s part when she claims that Monroe took still photography as seriously, if not more so, than film. The inimitable wiggle that she put on for the movie camera – ‘like Jello on springs’, as the Jack Lemmon character has it in Some Like It Hot – had its statuesque form in the poses she struck for the photographer’s lens … All the same, she was very choosy indeed when it came to the images she would allow to be printed.

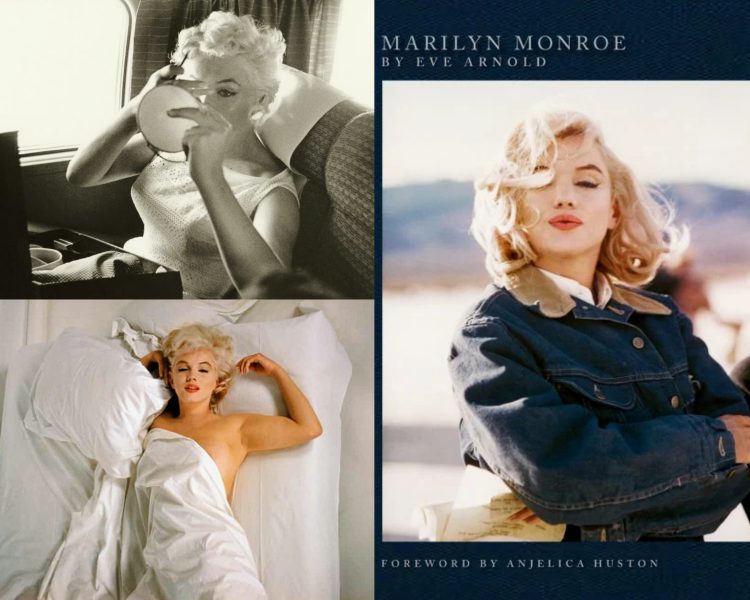

How did she get away with flaunting such raw sexuality? For no amount of airbrushing or euphemistic costuming could hide the fact, amply attested to in Arnold’s photographs of her, that this was a real woman … When she was not ‘being’ MM, many of the people she met did not recognise her and refused to believe she was Marilyn. Yet, when she was in front of the camera, she was luminous.

She knew from the start how vital to her success still photography would be; the photo magazines of the 1950s and 60s sold in the millions. By the time she met Eve Arnold she was a star, and could afford to relax, at least a little way, into being herself … In Arnold, both Marilyn Monroe and Norma Jeane Baker found their ideal imagist.”

Banville previously wrote about Marilyn on the 50th anniversary of her death in 2012…

“I first fell in love with her in River of No Return, in which she starred with Robert Mitchum and Rory Calhoun. The movie was released in 1954, and probably did not get to Ireland until the following year, so I was 10 when I saw it, at the Capitol Cinema in Wexford … the glory of the place, at least in my memory of it, was the great scarlet curtain, fluted and fringed, that would open with a deeply suggestive swish as the house lights dimmed and the dark screen came to flickering life.

For many years that curtain was associated in my mind with Kay Weston, the saloon-bar singer Marilyn played in the movie – no doubt the shade of rich red and the sumptuous, silken folds seemed the very essence of sexiness, for a boy who as yet knew nothing about sex … And yet, for all his fantasising, even that 10-year-old had an inkling of the reality behind the dumb-blonde persona, the creation of which was Marilyn’s masterwork.

By the time Marilyn threw herself and her hopes at the unprepossessing figure of Lee Strasberg, her image as MM the blonde bombshell was thoroughly reified, at least in the eyes of a mesmerised public. Having fashioned this more-than-lifesize image of herself, how could she expect to unmake it and start again, reappearing in the guise of a dedicated actor capable of taking on tragic roles?

If she could, she would have lived inside a camera. One suspects that for Marilyn, her image was more real than her self. The depth of her self-absorption was uncanny. A friend told of passing through her house and seeing her sitting in front of a mirror, gazing at her reflection, and then returning some time later to find her still there, still at gaze. ‘I’m looking at her,’ Marilyn explained.

Few of us could bear such an acute awareness of our physical presence in our own lives; perhaps, in the end, she could not bear it, either. Yet she had a genius for cultivating the camera, and cameramen – and they were all men, with few exceptions; Eve Arnold, who took some wonderfully intimate, tender and witty pictures of her, was one of the few women photographers Marilyn trusted.”