Audrey Flack, the American artist known for her photorealist style, died aged 93 on June 28, 2024.

She was born in Manhattan in 1931 to Polish immigrant parents who owned a garment factory. In 1952, she began studying fine arts at Yale University.

Her early paintings were abstract expressionist, but she later became a New Realist, and in 1966, she was the first photorealist painter added to the collection of the Museum of Modern Art.

She was also featured in ‘Some Living American Women Artists,’ Mary Beth Edelson’s 1972 collage based on Leonardo Da Vinci’s 15th century painting, ‘The Last Supper.’

In 1976, Flack began a two-year project. Her Vanitas series was inspired by the symbolic still-lifes of 17th century Flemish painters, with each work referring to the Latin concept of momento mori. In ‘Wheel of Fortune,’ she confronts her own mortality; while ‘World War 2’ revisits the Holocaust.

15 years on from her death aged 36, Marilyn was another subject for Vanitas. In her 1977 painting, Marilyn, Flack recreated a famous photo by Andre de Dienes of Marilyn in 1949. Although on the cusp of fame, she had darker hair and less make-up, and was still recognisably Norma Jeane.

The image is shown within an open book, opposite a slightly tilted replica in an oval frame. Both objects are placed on red fabric alongside a lit candle, evoking memories of Elton John’s ‘Candle in the Wind’.

There are also items related to the art of glamour, such as a tube of lipstick and compact mirror; and a string of pearls inside a blue wineglass.

A calendar page reminds us of Marilyn’s nude pin-up, but is turned to August 1962, when she died; an hourglass alludes both to her shapely figure and the passing of time, while a small alarm clock denotes both her chronic lateness and sudden demise.

Framed with grapes and a red rose – the same flower Joe DiMaggio had delivered to Marilyn’s grave every week for twenty years – the painting also includes other ‘perishables’, such as two pears, and an orange cut in half. Finally, a childhood photo of Flack serves as an artist’s signature, and a reminder of lost youth.

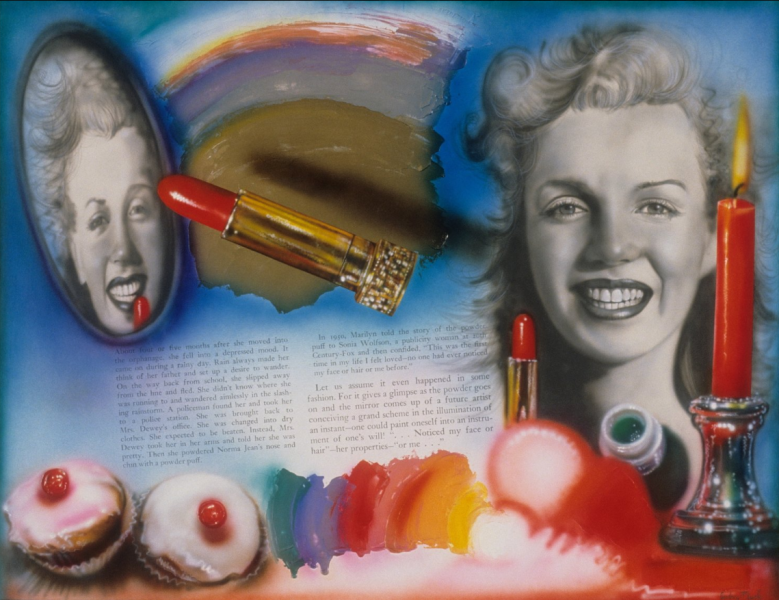

Another painting, Marilyn: Golden Girl, sets the same double-portrait against a sky-blue background, and a page from a book recounting a story about Norma Jeane running away from the orphanage. Expecting punishment, she is met with kindness when the matron, Mrs Dewey, powders her face.

A gold lipstick tube points towards the framed double, with shades of red below positing Marilyn as the ‘artist’ behind the image. The candle still burns, and two sticky buns with cherry nipples reflect Monroe’s playful sensuality.

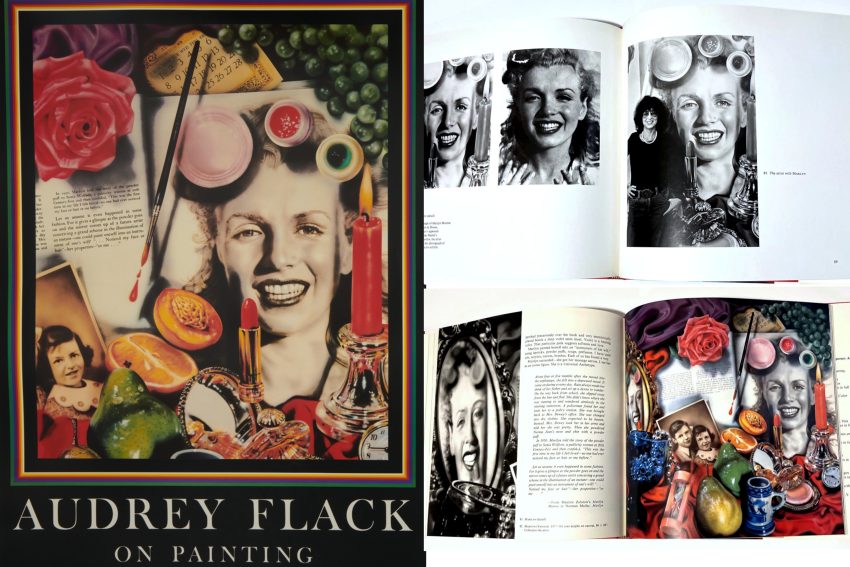

‘Vanitas: Marilyn’ made the cover of Flack’s 1981 monograph, On Painting; and in 1987, Carl Rollyson chose it for the first edition of his biography, Marilyn Monroe: A Life of the Actress.

“Marilyn narrates Monroe’s life in the sense that she faces us as an image … Her expression is enthusiastic, but this is truer of the original photograph than of the painting, for Flack has lined Monroe’s brow with a slight trace of pain. The calendar is turned to August, the month of Monroe’s suicide, and the black end of the paintbrush points to the day she died. The flower, the fruits, the luxuriance of the drapery, the bold colours – especially the reds – evoke memories of the colour schemes of Monroe’s movies and of her photographs, especially the nude calendar shot of 1949. But these are Flack’s colours as well, colours that dominate many of her other paintings and that are especially prominent in her Vanitas series, of which Marilyn is a part. The point of Vanitas, Flack explains, is to ‘encourage the viewer to think about the meaning and purpose of life.’ The meaning of Flack’s life is also indicated by her inclusion of a photograph of herself as a child and by the paintbrush with its drops of paint on the paperback text of Norman Mailer’s biography of Monroe …

Flack shows that there is a natural progression from Mailer’s text (which is about Monroe’s childhood discovery of makeup), to the photograph of Monroe (which represents what the actress has made of herself for the camera), to the whole painting’s vision of the need for self-definition, the need for one artist to inspire another artist to inspire another artist, and so on. By depicting Monroe’s reflection in a domestic context – in a dressing-table mirror – Flack forces us to probe our own desire for recognition, so that we can see ourselves in a larger world. Monroe’s distorted image (notice how her face takes on the shape of the oval mirror) makes manifest the ways in which the self’s own shape is twisted, magnified, elongated, and blurred in the process of reproduction. Although this painting is very specifically about one woman’s replicated life, it can also be read as the story of the underlying motivations that drive all people to be creative, to fashion the largest possible sense of themselves.”

By the 1980s, Audrey was also working in sculpture, with baroque art succeeding photorealism as her dominant influence. She created a bronze statue of Catherine of Braganza, for whom the New York Borough of Queens is named. Due to Catherine’s involvement in the slave trade, it was relocated to Lisbon.

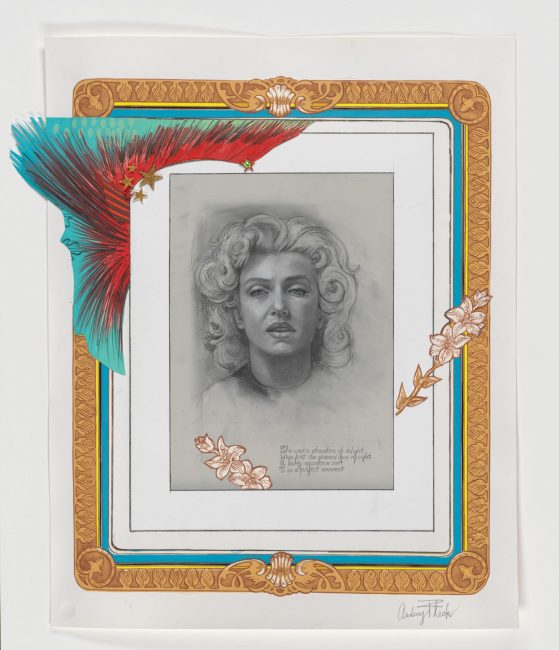

An accomplished banjoist, Audrey released an album with her History of Art band in 2012. Her 2015 exhibition, Heroines, featured a ‘transcendent drawing’ of Marilyn. Based on a 1953 photo shoot with Ben Ross, the portrait shows a tougher Monroe. The pencil drawing is framed in gold and decorated with feathers, and lines of verse by the Romantic poet, William Wordsworth (‘She was a phantom delight …’)

Audrey Flack’s memoir, With Darkness Came Stars, was published shortly before her death in Southampton, NY.

1 Comment

Comments are closed.