Artist Natalie Krick reimagines one of Marilyn’s most iconic photo shoots in a new exhibition, on display at the Frye Museum in Seattle until April 6.

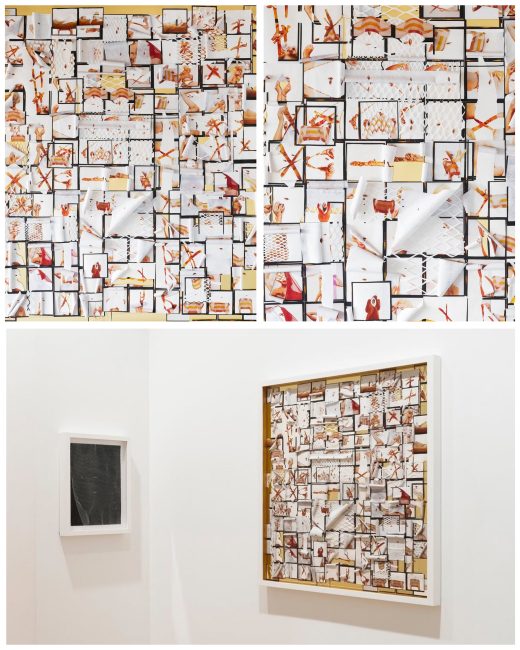

“In her new suite of collages for the Boren Banner Series, Natalie Krick deconstructs pictures of Marilyn Monroe. Using contact sheets from commercial photographer Bert Stern’s The Complete Last Sitting (a book of 2,600 photos taken for Vogue magazine six weeks before the actress’s death), Krick separates the images from the book’s eroticised language. She then obscures them by masking, layering, and applying cut-out patterns—interventions that complicate the voyeuristic viewing the book imposes on its iconic subject.

The Boren Banner Series reflects the museum’s commitment to showcasing work by Pacific Northwest artists. This biannual series gives regional artists the opportunity to present a piece as a monumental, 16 x 20 ft. vinyl ‘banner’ alongside an exhibition of related works inside the museum. The billboard-size artwork is prominently sited facing Boren Avenue, the Frye’s most visible and accessible physical interface.”

Natalie discussed the exhibition in an interview for The Stranger.

“‘I never wanted to be Marilyn—it just happened. Marilyn’s like a veil I wear over Norma Jeane.’

A frail latticework extends over a face in black and white that we’ve seen a million times, casting a netted shadow, obscuring familiarity with precision. You want to squint, walk up, to it and cast it aside, but its fluidity is only an illusion—the veil is immovable, unable to be pierced. More of an armor than an invitation. It’s made up of the woman underneath, of thousands of photos of one of the most photographed people of all time: Marilyn Monroe.

‘Our generation is references on references,’ Krick explains. And Marilyn Monroe is the best example of it. ‘I was realising that so many famous women since her time have been photographed as Marilyn Monroe.’

Krick elaborates that she never set out to attach to Monroe, especially after a lifetime of being inundated with her image. But after a while, a new dimension to that exposure surfaced. ‘She’s so iconic, and it’s why I was so drawn to her,’ she says. ‘I was thinking a lot about how women are sexualised in photographs, how our sexuality is posed and dressed up. I think it has to do with this idea that women aren’t sexual on their own—that you can’t be sexual on your own.’

Stern, the photographer of The Complete Last Sitting, wrote an accompanying essay in the anthologised version of selects of those photos. His language is possessive, horrifying in its unflinching reflection of how Monroe and all women were digested through the lens and through the machine of public life. ‘It feels relevant, the way he sexualised her,’ Krick reflects. ‘The way he made her into this seductive witch who enchanted him, who is also this tragic, one-dimensional person. It’s one of the reasons why I felt like I needed to work with those photographs. Thinking about how much those photographs are really about him.’

The photos are cut up, but the presence is enormous. ‘One of my rules for myself is that I wanted all the photos of Marilyn to be life-sized,’ Krick says. ‘I think about the body and my body so much; that scale seems important to me for how people experience it.’

Krick knows that ‘reclaiming’ Monroe’s ‘truth’ is none of her business, and presuming that it’s possible, or even that Monroe would want a public in her head, is counterproductive to what is left of her legacy. ‘I’m making her veil the way she spoke about it, making her into the photographer, into the person who views rather than is being viewed,’ she says.

The texture in Krick’s piece reminds you of that tension—a veil as self-protection, an intricate piece, as something woven out of air and permeable. Her care in allowing space for Monroe to hide and to reveal is played not as coy, but as dynamic.

‘I don’t really take pictures anymore, but for this, I took pictures of [Stern’s] pictures,’ she says. ‘It’s been quite a while since I’ve made “portraits.” I guess over the years, I’ve become more suspicious about portraiture. I love it—it’s not like I think it shouldn’t exist. But one of the reasons I started to use his work was because I was really upset about the way he wrote about her [in that book]. He frames her as this tragic figure, and that’s how she’s framed in our culture. I do see her death as tragic, but I don’t see her as tragic. She was an artist who doesn’t get what she deserves.'”

And finally, The Beacon cinema is partnering with the Frye Museum in Seattle for a season of four Monroe films, with Gentlemen Prefer Blondes starting a week-long run tomorrow, February 23. Some Like It Hot follows on March 2, with Niagara from March 9, and The Misfits on March 16.

1 Comment

Comments are closed.