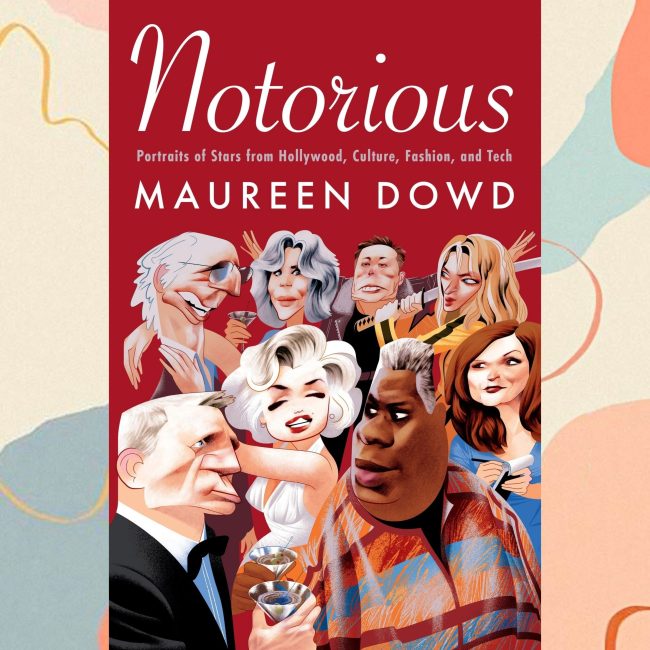

A selection of New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd’s celebrity profiles are featured in a new book, Notorious. André Carrilho’s cover illustration – perhaps inspired by legendary caricaturist Al Hirschfeld – shows Marilyn in a white halter dress, with her arms draped around comedian Larry David. Among the other celebrities featured is Jane Fonda, who met Marilyn as a young actress; and the author herself (with pen and paper at the ready.)

While Dowd never met Monroe, she wrote of her approvingly in a 2010 article, ‘Making Ignorance Chic,’ praising her lifelong quest for self-improvement in contrast to what Dowd characterised as the wilful ignorance of contemporary figures like Sarah Palin and Kim Kardashian. (Ironically, Dowd’s own attacks on women in the public eye led to accusations of sexism from New York Times editor Clark Hoyt.)

Dowd went on to present a BBC radio documentary, The Smart Dumb Blonde, on the 50th anniversary of Marilyn’s death in 2012. ‘Musing on Marilyn Monroe,’ Dowd’s essay for Notorious, draws upon several articles, including her review of Fragments, the 2010 collection of Marilyn’s letters, notes and poetry; and her thoughts on Michelle Williams’ Oscar-nominated performance in My Week With Marilyn (2011.)

Dowd begins with a reminiscence from comedy writer turned director Mike Nichols.

“It was the mid-1950s, and they were both taking an acting class in New York with Lee Strasberg. Nichols recounted his conversation with the woman with the familiar breathy voice: ‘The phone rang and somebody said “Hello,” and I said, “Hi, is Marilyn there?” and she said, “No, she’s not,” and I said, “Well, this is Mike. I’m in class with her. Could you take a message?” And she said, “Well, it’s a holiday,” because it was the Fourth of July weekend, and that, to her, was an excuse for not taking a message for herself.’

No one ever said Marilyn wasn’t complicated …”

A recent biography of Richard Avedon, Something Personal, includes another anecdote from Nichols about when he and the photographer visited Marilyn’s New York apartment to persuade her to appear on a CBS television special, The Fabulous Fifties. Nichols hoped to write a skit for Marilyn, but her husband Arthur Miller “nixed” the idea.

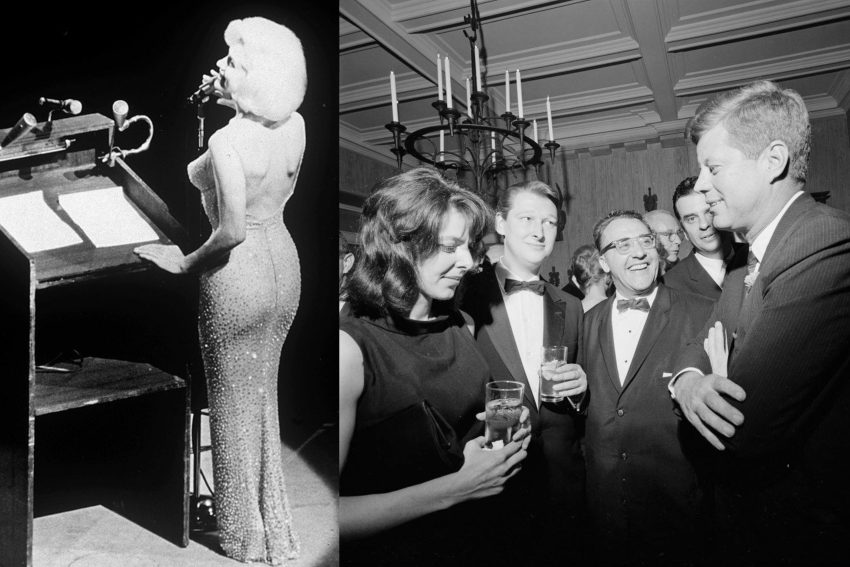

In 1962, Nichols and his comedy partner Elaine May were among the performers at the Democratic fundraising gala for President Kennedy’s 45th birthday at Madison Square Garden. “I was standing right behind Marilyn Monroe, completely invisible, when she sang ‘Happy Birthday Mr President,'” he told Maureen Dowd. Nichols went on to claim that Marilyn’s dress split, and that she was nude underneath. (The first part is untrue, as the dress remained intact – or at least it did until Kim Kardashian wore it to the Met Gala in 2022.)

He also mentioned attending the after-party at the Manhattan apartment of Arthur B. Krim, who organised the event. “Elaine and I were dancing, and Bobby Kennedy danced by us,” he recalled, “and I swear to God the conversation was as follows: [Here Nichols put on, first, a feathery voice and then a nasal one] ‘”I like you, Bobby.” “I like you, Marilyn.”‘

In 2012, Dowd asked the director – who had worked with many famous beauties – if he could explain her staying power.

“‘I think that the easiest answer might be that she had the greatest need,’ he said. ‘She wasn’t particularly the greatest beauty, that is to say, Hedy Lamarr or Ava Gardner would knock the hell out of her in a contest, but she was almost superhumanly sexual.’

Arthur Gelb, the former Times managing editor, likes to tell how he won a $10 bet as a slightly inebriated rewrite man in the ’50s when he reached out and, much to her annoyance, touched Marilyn’s flawless porcelain back as she dined with friends at Sardi’s.

‘When she walked, it was as though she had a hundred different body parts that moved separately in different directions,’ he told me on the BBC show. ‘I mean, you didn’t know what body part to follow.'”

Dowd also addresses the sexual objectification of Marilyn in her essay.

“Photographers loved to get her to pose in tight shorts, a silk robe or a swimsuit with a come-hither look and a weighty book, a history of Goya or James Joyce’s Ulysses or Heinrich Heine’s poems. A high-brow bunny picture, a variation on the sexy librarian trope. Men who were nervous about her erotic intensity could feel superior by making fun of her intellectually.

Marilyn was not completely in on the joke. Scarred by her schizophrenic mother and dislocated upbringing, she was happy to have the classics put in her hand. What’s more, she read some of them … At least, unlike Paris Hilton and her ilk, the Dumb Blonde of ’50s cinema had a firm grasp on one thing: It was cool to be smart. She aspired to read good books and be friends with intellectuals, even going so far as to marry one.”

And finally, Dowd looks back on the sale that brought Marilyn’s legend into the 21st century.

“The celebrity-drenched culture that dawned in the age of Marilyn, J.F.K. and Jackie reached nauseating new depths in a world obsessed with celebrity lifestyle and deathstyle.

Back in 1999, I covered the display for the Christie’s auction of Marilyn’s personal property. It was invasive and inviting at the same time … Some of the Marilyn stuff, bequeathed by the star to her acting teacher, Lee Strasberg, and sold by his widow, Anna, was glamorous … Here are her scripts with pencilled notes to herself, like the scene in Some Like It Hot when she tells herself to act ‘delighted’ when she gets on the yacht with Tony Curtis.

Her ambitious library got its own room … The ‘nudest dress,’ as the designer Jean Louis called that skin-tight, flesh-tone, rhinestone-dotted gown that Marilyn wore to Madison Square Garden – was reverently displayed in a room by itself, lit from above as though it were the Pieta or the David.

Curators told me that they had to send for a petite mannequin from Paris … But other Marilyn items on display at Christie’s were forlorn: her Mexican sombreros, her certificate of conversion to Judaism when she married Miller, her platinum-and-diamond ‘eternity band’ from DiMaggio, her heart-shaped cookie cutters, her poem entitled ‘A Sorry Song.’

‘It’s great to be alive, they say I’m lucky to be alive,’ she wrote in pencil in one melancholy notation. ‘It’s hard to figure out when everything I feel – hurts!’

But it was, after all, Marilyn’s troubles that kept her so compelling. As the actress said in Some Like It Hot, she always got stuck with the fuzzy end of the lollipop.”