The English pop artist Richard Hamilton’s ‘My Marilyn’ (1965) is currently on display at the Holburne Museum in Bath (until May 5th) as part of Iconic: Portraiture from Francis Bacon to Andy Warhol.

“The exhibition focuses on the period in the mid 20th century, particularly the 1960s, when many artists began to use photographs as sources for paintings. Often, the photographs were not simply appropriated as tools in picture making but were themselves the subject matter, resulting in paintings that are about imagery and the mediation of such images. The exhibition also reflects on the potency of the media and the construction of celebrity. Many artists used photos of celebrities as the basis of their works, and several illustrate a degree of nostalgia, even for the very recent past.”

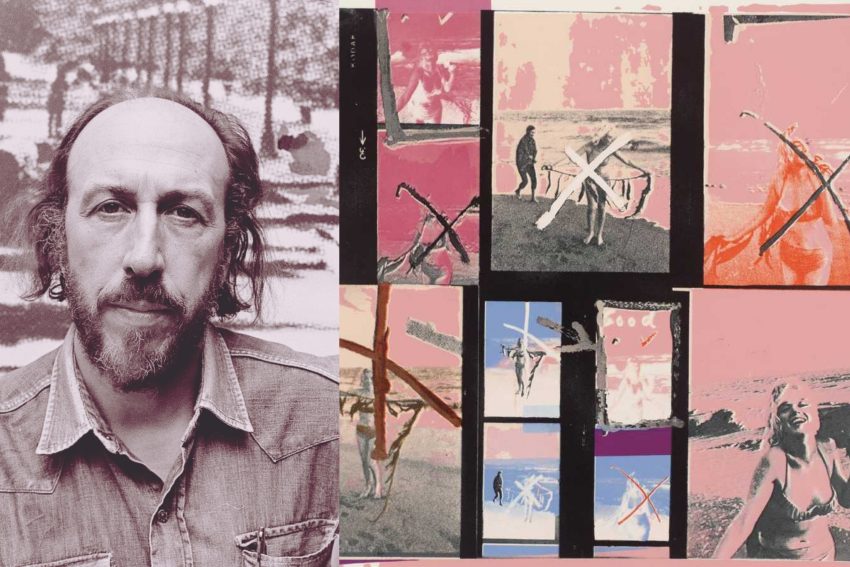

Richard Hamilton was born in London in 1922. After working as a technical draftsman during World War II, his artistic breakthrough came in 1956 (the same year that Marilyn filmed The Prince and the Showgirl in England), when his work was featured in This is Tomorrow, a seminal group exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery.

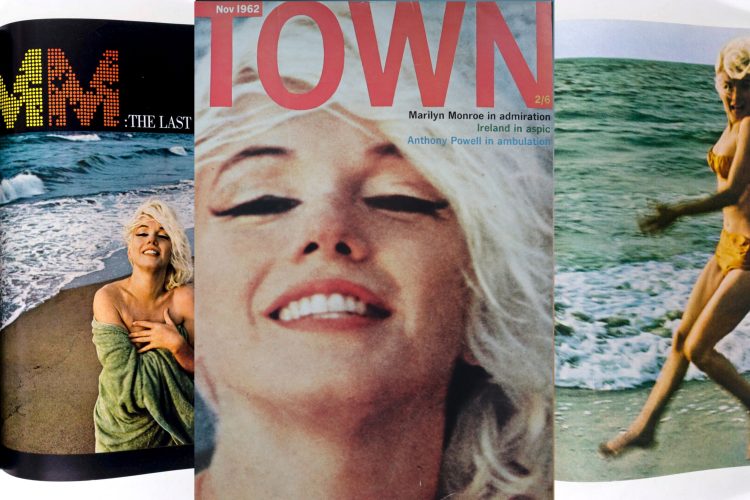

In 1962, TOWN magazine featured Marilyn in its November issue, following her death three months before. Another early pop artist, Pauline Boty, used the cover photo as the basis of her painting, ‘Colour Her Gone.’

Hamilton was also inspired by the layout from one of Marilyn’s last photo sessions with George Barris, shot on Santa Monica Beach in June 1962. Barris had interviewed Marilyn for Cosmopolitan, and after she died, his articles were serialised by newspapers on both sides of the Atlantic.

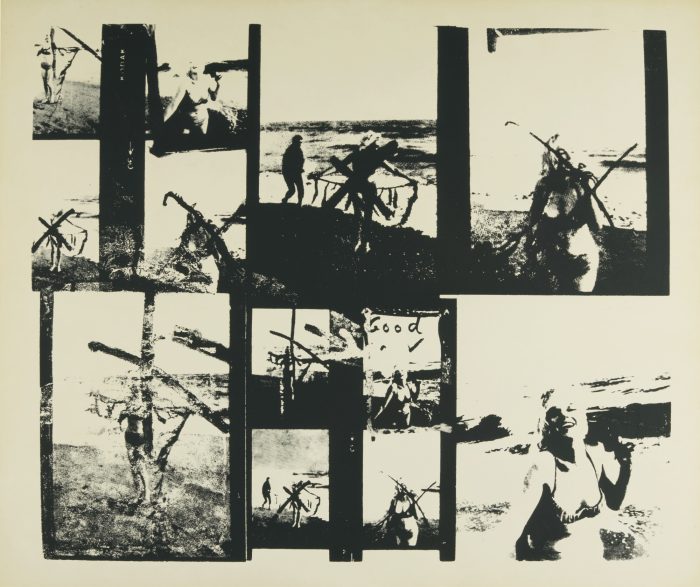

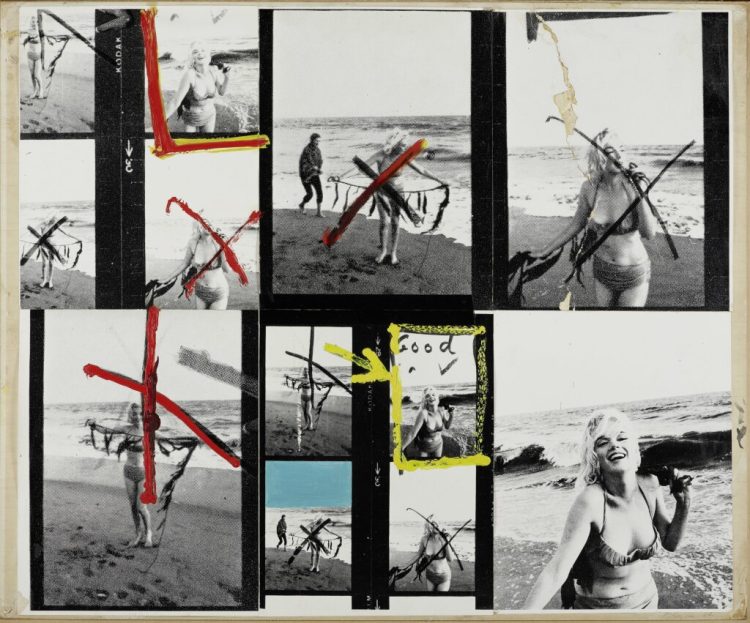

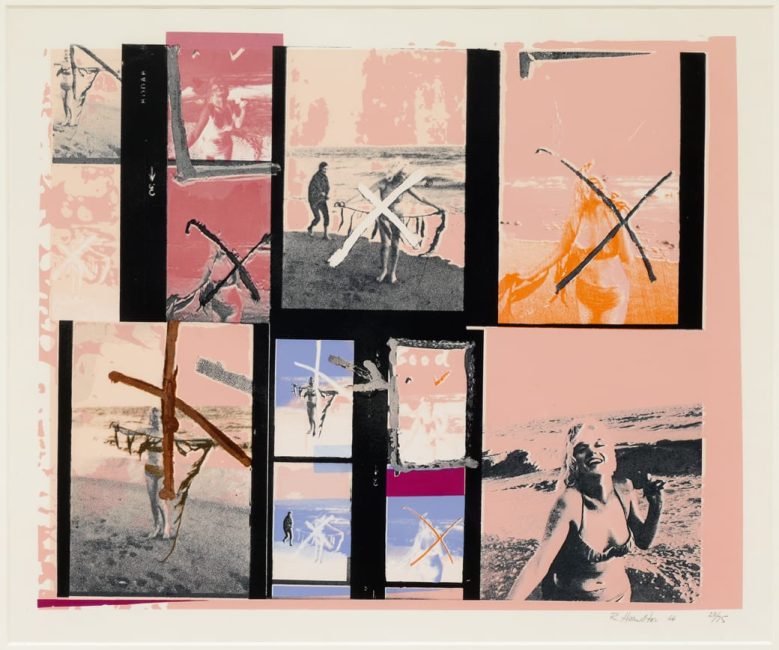

However, Hamilton was less interested in the finished product than the work in progress. Possibly named after bandleader Ray Anthony’s 1952 single, ‘My Marilyn,’ the collage is based on a contact sheet (or a mockup thereof), complete with Marilyn’s revisions – including crosses scrawled over images she disliked.

Hamilton was perhaps the first artist to recognise the creative potential of these outtakes. Another photographer, Bert Stern, later went further by showing his rejected images as Marilyn had left them. Art historian Griselda Pollock has likened her markings to a ‘painterly gesture‘, thus reclaiming her image from the intrusive lens.

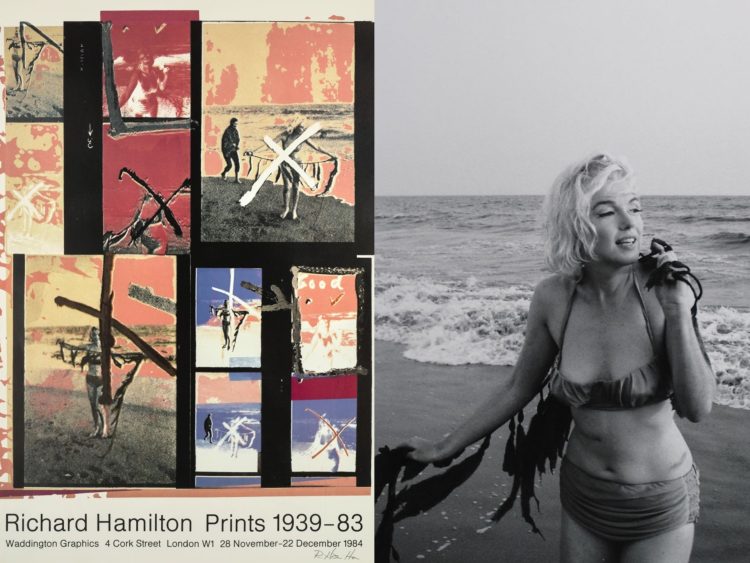

In 1984, Hamilton used ‘My Marilyn’ as poster art for a London retrospective. Barris released prints of the unapproved images with Marilyn’s crossings removed (see below, at right.) In 1999, he sued Hamilton for copyright infringement, but his case was unsuccessful.

After Hamilton’s death in 2011, Hal Foster wrote about his work, including ‘My Marilyn,’ for the London Review of Books.

“Hamilton explored the new relay between self and image directly in his own version of the ultimate Pop icon, Marilyn Monroe, made after his first visit to the United States in 1963, where he travelled with his friend Marcel Duchamp, and met Andy Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, Ed Ruscha and other young bucks of American Pop art. In ‘My Marilyn’ (1965) Hamilton adapted, in painting, part of a contact sheet from a photo shoot by George Barris that included her own editorial indications as to which images to cut and what pose to permit – in short, how to look, to appear, to be. In the rough grid of the painting a cluster of four images appears twice, with slightly different markings and croppings, once at upper left and again, a little smaller, at centre bottom; each of the images also appears, enlarged, with further alterations by Hamilton, in the other rectangles of the painting. The most dramatic changes are wrought on the one image approved by Marilyn (marked ‘good’): here the colour is that of a deteriorated photograph (the sky and the sea are two bands of lurid pink and orange), and her body is whited out, as if in negative, as if she were already absent (as indeed she was in 1965). Although the Marilyn commemorated by Hamilton is still a star, she is less an erotic object than an anxious designer, the stringent artist of her own powerful iconicity, a merciless editor of her own public appearance. Perhaps Hamilton identified with this editorial rigour; certainly he agreed with her implication that being is imaging in the Pop age.

How different this relation to Monroe is – more pointed, in my view, more poignant – from the agitation acted out by de Kooning or the thrall suggested by Warhol. Hamilton elaborates not only on the expressive possibilities that Marilyn offered (apparently she would mark her contact sheets with whatever was at hand – lipstick, nail-file, scissors) but also on the psychological states that she evoked, which range, in his words, from the ‘narcissistic’ to the ‘self-destructive’. All at once Marilyn appears to desire, even to solicit, our gaze (that this gaze is captured is the sine qua non of celebrity), and to fear, even to refuse it (rightly so, perhaps, given that her masochistic marking seems to anticipate our invasive looking). In this regard we might compare ‘My Marilyn’ with the other great Hamilton essay on the problematic glare of celebrity, ‘Swingeing London 67’ (1968), his lurid painting of Mick Jagger and Robert Fraser (an art dealer of the time) manacled together in a police van after a drug bust.”

Writing for the Tate website in 2023, however, Jacqueline Rose (whose 2014 book, Women in Dark Times, includes an extended essay on Marilyn) has argued that Hamilton’s depiction is less powerful than Pauline Boty’s ‘The Only Blonde in the World’ (1962.)

“How to create an image of a woman without making her a slave to beauty? How to bring a woman, who is already an icon, to life? If Marilyn Monroe has taught us anything, it is that public adoration kills as much as it reveres. In the early 1960s, Pauline Boty and Richard Hamilton were transfixed. Boty marched on a CND demonstration alongside Hamilton who was carrying a life-sized cut-out of Monroe, and each of them painted Monroe – or rather painted across one or more of a multitude of existing images – at a similar time … And yet, as these two works make clear, their passion for Monroe assumed very different artistic shapes. Hamilton used a contact sheet of photos by George Barris, taken shortly before her death. This had been marked by Monroe with crosses and ticks to indicate her approval and disapproval (mostly the latter), scoured in places with scissors almost to the point of obliteration – images that Hamilton cuts and pastes, overlays with colour, and blurs. Some critics have seen the work as giving back to Monroe a ‘hint’ of agency. He himself described the work as a testimony to self-destruction, which made ‘her death all the more poignant.’ Either way, he was making his mark over her own … If Hamilton’s position is one of ownership (the title ‘My Marilyn’ is surely the giveaway), Boty seems to take the riskier, more intimate, path of identification.”

And finally, Anna McNay has reviewed ICONIC for Studio International…

“This small, one-room exhibition at the Holburne Museum in Bath has considered every angle and every detail and the result truly is a bijou gem … Sexuality is underlined by […] the proliferation of Marilyns in Hamilton’s print, made from 11 stencils. Like a contact sheet, it showcases the actor’s well-known attempts to control her promoted image by scrawling over photos of herself that she did not like. This work, synchronous with Warhol’s multiplied Marilyns, was made using a set of photographs that Hamilton saw in a magazine a few months after Monroe’s death. Everything about it screams similarities with contemporary social media and the growing list of influencers who have killed themselves … The exhibition presents a concise remit and, in just 22 works, more than does it justice.”