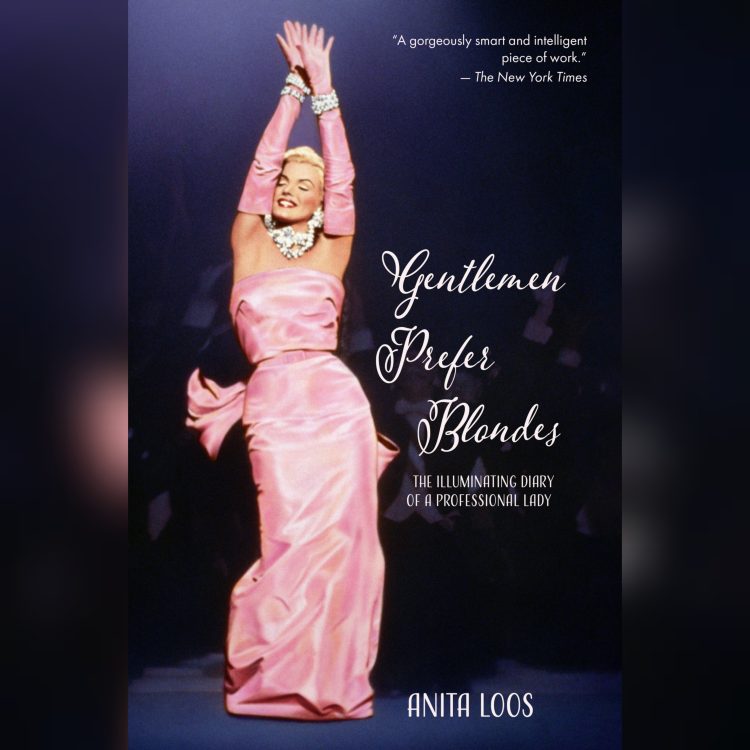

Anita Loos’ Gentlemen Prefer Blondes: The Illuminating Diary of a Professional Lady was published 100 years ago and remains in print today. The Warbler Classics edition pictured above, released in 2021, shows Marilyn as Lorelei Lee, singing ‘Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend’ in the 1953 movie.

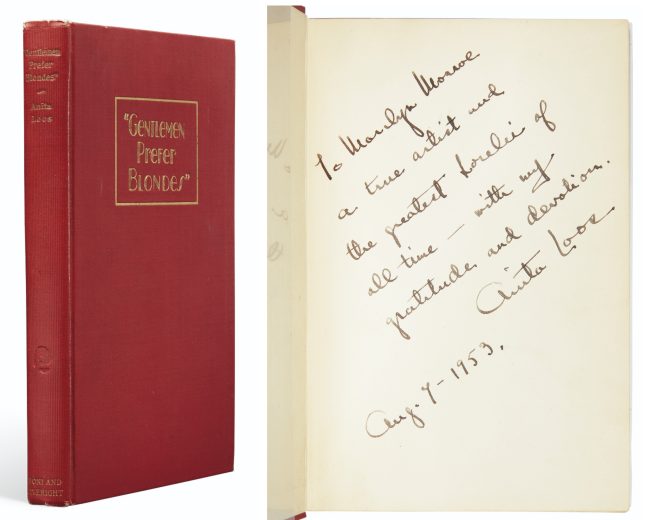

A first-edition copy inscribed by the author was sold for $16,250 at Christie’s in 1999, as part of the estate auction, The Personal Property of Marilyn Monroe. The inscription reads thus: ‘To Marilyn Monroe/a true artist and the greatest Lorelei of all time – with my gratitude and devotion, Anita Loos.’

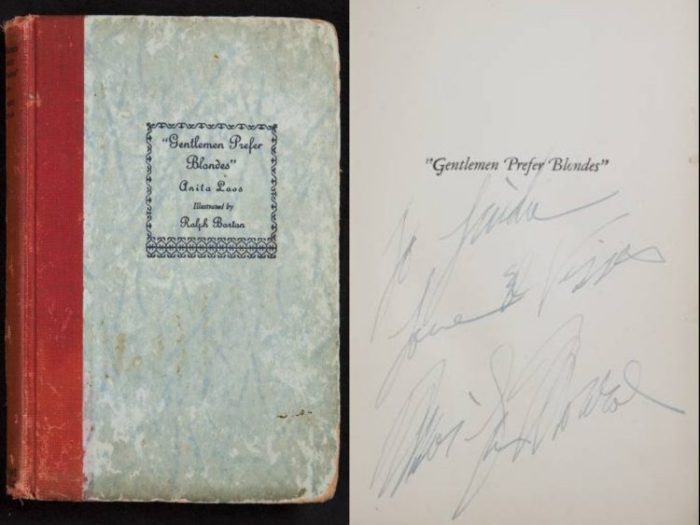

And this 1926 reprint was inscribed by Marilyn to child actress Linda Bennett (The Big Heat), and sold for $10,000 at Julien’s Auctions in 2012. The inscription reads: ”To Linda/Love and Kisses/Marilyn Monroe’.

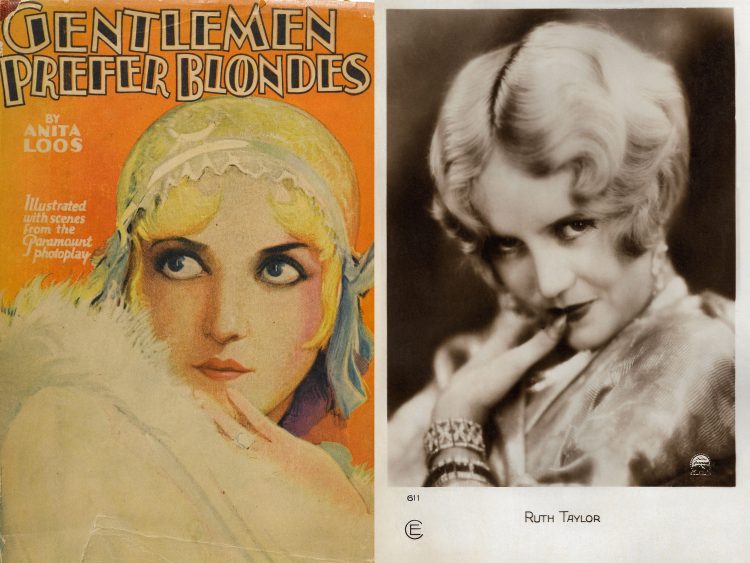

Ruth Taylor was the first actress to play Lorelei onscreen, in a silent movie which is sadly now lost.

“Miss Taylor has big blue eyes and, being quite a clever actress, she is able to make them sparkle at the mere suggestion of precious stones … [She] has grasped to perfection Lorelei’s calculating characteristics.”

– Mordaunt Hall, New York Times (1928)

“Miss Monroe looks as though she could glow in the dark, and her version of the baby-faced blonde whose eyes open for diamonds and close for kisses is always amusing as well as alluring.”

– Otis L. Guernsey Jr., New York Herald Tribune (1953)

Writing in The Times yesterday, John Self claimed that Gentlemen Prefer Blondes holds its own among loftier tomes from 1925, such as F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby.

“As valuable a portrait of the fizz-headed jazz age as Fitzgerald’s work, this is the diary of the girl-about-town Lorelei Lee. Her breathless style (most sentences begin ‘So…’ or ‘I mean…’) and cute misspellings add to the charm as we flit from New York to London and Paris, with Lorelei’s bitchy friend Dorothy in tow. Discussing perfume brands, she tells us: ‘So then Dorothy said that she supposed Mr Coty came to Paris and smelled Paris and he realised that something had to be done.’ Lorelei is taken advantage of by the wealthy men she’s attracted to, but gets her own back in the end. ‘I mean [Dorothy] said my brains reminded her of a radio because you listen to it for days and days and you get discouradged [sic] and just when you are getting ready to smash it, something comes out that is a masterpiece.'”

Michelle Stacey took a closer look at Gentlemen Prefer Blondes and its author in ‘Loos Woman’, a recent article for the Air Mail website, detailing how the original story differed from the 1953 movie, which was based on a Broadway musical adaptation that Loos co-wrote.

“Now almost entirely identified with the 1953 Marilyn Monroe film it inspired, the book was a powerhouse in its time, first taking the country by storm in the summer of 1925 as a monthly serial in Harper’s Bazaar (where it doubled, then tripled, the magazine’s circulation). Published as a book in November of that year, it sold out on its first day; the second printing, of 60,000, was quickly snapped up as well, and it was the No. 2 best-selling novel in 1926. (By contrast, The Great Gatsby had already been remaindered by late 1925, with sales peaking at 20,000.)

Loos’s story, told in the unsophisticated voice of its protagonist, is a flapper-era take on the male-fortune-seeking tradition that goes back to 18th-century English satirist Henry Fielding’s novel Tom Jones and William Thackeray’s Barry Lyndon a century later. Lorelei’s diary takes her and Dorothy on a madcap tour of Europe, funded by Lorelei’s much older ‘gentleman friend,’ otherwise known as ‘the Button King.’ His stated aim is to ‘educate’ Lorelei, as he can tell she has ‘brains’; her secret aim is to secure her future.

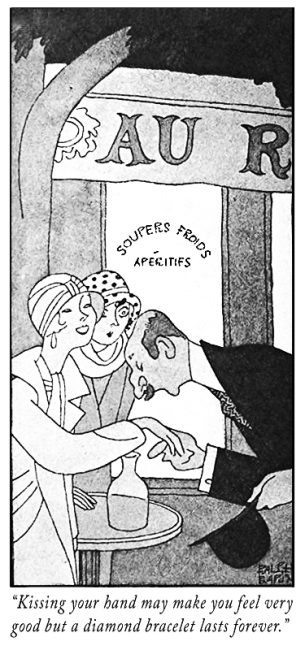

The diary chronicles the two strivers’ social and romantic adventures, from London (‘not so educational after all’) to Paris (‘devine,’ in part because it has ‘all of the famous historical names, like Coty and Cartier’) to ‘the central of Europe,’ where Lorelei meets with ‘Dr. Froyd’ (‘He seemed very very intreeged at a girl who always seemed to do everything she wanted to do’). What Lorelei wants to do is receive expensive gifts (‘Kissing your hand may make you feel very very good but a diamond and safire bracelet lasts forever’) and achieve a lucrative marriage.

The story is replete with Lorelei’s constant misspellings, self-conscious attempts at grammar (‘a girl like I’), and frank acknowledgments of her avariciousness, which never occurs to her as a fault but rather as a necessity. The reader is not sure whether to laugh at Lorelei or with her—or both.

To its author, the laughing itself was the point. As Loos confessed in an introduction to a later edition of Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, ‘I, with my infantile cruelty, have never been able to view even the most impressive human behaviour as anything but foolish…. My slant on life [is] that of a child of ten, chortling with excitement over a disaster.’

A tiny brunette who topped out at under five feet and around 90 pounds, Loos, who was born in Northern California in 1889, used her rapier wit and finely tuned sense of the absurd to punch above her weight throughout a long career as a screenwriter, playwright, and novelist.

Gentlemen Prefer Blondes brought her fame that included breathless news stories about her every Atlantic crossing, raves from the English royal family (the Prince of Wales reportedly bought 19 copies), and introductions to leading lights in literature, journalism, Hollywood, and the European aristocracy.

Fitzgerald’s lens on the Roaring 20s was tragedy; Loos’s was comedy, a historically under-appreciated genre. She was onto all this, writing in 1974 that, ‘with such material’ as Lorelei’s story, ‘Scott Fitzgerald would have shed bittersweet tears over such eventualities.’ Tears, it seems, can leave a more lasting impression than laughter. But all things considered, Loos may ultimately have agreed with Lorelei Lee’s Panglossian assessment: ‘Everything always works out for the best.'”

And finally, you can read more about Gentlemen Prefer Blondes on page, stage and screen here and at The Marilyn Archive.