Two images from a photo shoot accompanying Marilyn’s final interview are featured in a new exhibition, now open at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York until June 21, 2026.

“The Museum of Modern Art announces Face Value: Celebrity Press Photography, the first major exhibition of Hollywood studio portraiture to be drawn from the Museum’s film stills archive since 1993. On view in the Titus and Morita Galleries, the exhibition will offer a revisionist look at the Department of Film’s photographic archive, examining the evolution of editorial practice before the digital age, AI technology, and social media reshaped the experience of celebrity. Face Value will feature over 200 works from 1921 to 1996, including studio photography of Louis Armstrong, Harry Belafonte, Clara Bow, Louise Brooks, Bette Davis, Mia Farrow, Katharine Hepburn, Dennis Hopper, Lena Horne, Bela Lugosi, Carmen Miranda, Elvis Presley, Diana Ross, Barbara Stanwyck, Elizabeth Taylor, Spencer Tracy, Oprah Winfrey, and many others.”

Curator Ron Magliozzi has discussed the exhibition in an interview for the New York Observer.

“In the early days of Magliozzi’s career at MoMA, he worked in the warehouse, separating press material from photographs. He recalled a curator commenting that since many photographs were marked up, they were spoiled—unfit for exhibiting and uninteresting. But Magliozzi felt that the etchings and drawn-in dimensions added something, highlighting the photographs as working documents.

These ‘flaws’ are indeed the most interesting parts of the exhibition. In some photographs, white ink silhouetting adds an eeriness: the heads of the subjects seem to float or hover. In others, lines of tape mark image croppings … present are photographs with masking, inpainting and collaging.

The backs of the photographs are equally compelling, he asserts, with their marks, stamps and notations indicating their provenance. The images come chiefly from two editorial collections: Photoplay (1911-80) and Dell (1921-76), both legendary Hollywood publications whose archives were acquired by early MoMA film curator Iris Barry.

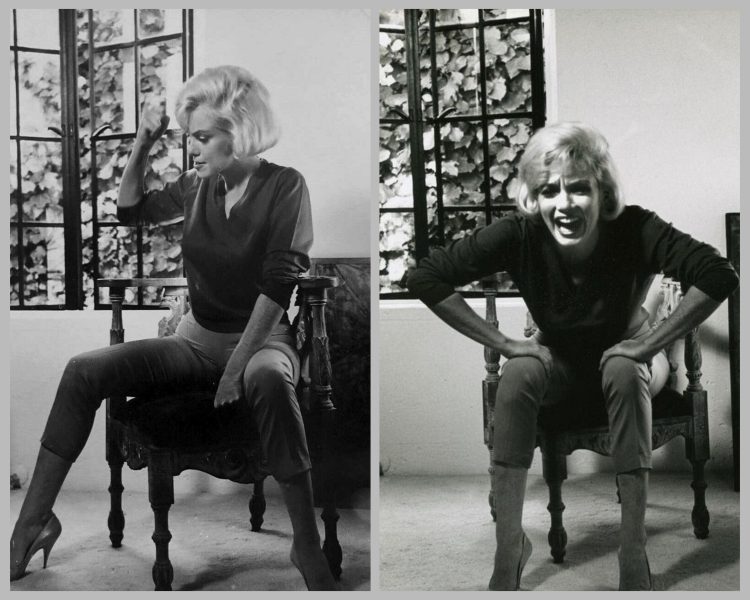

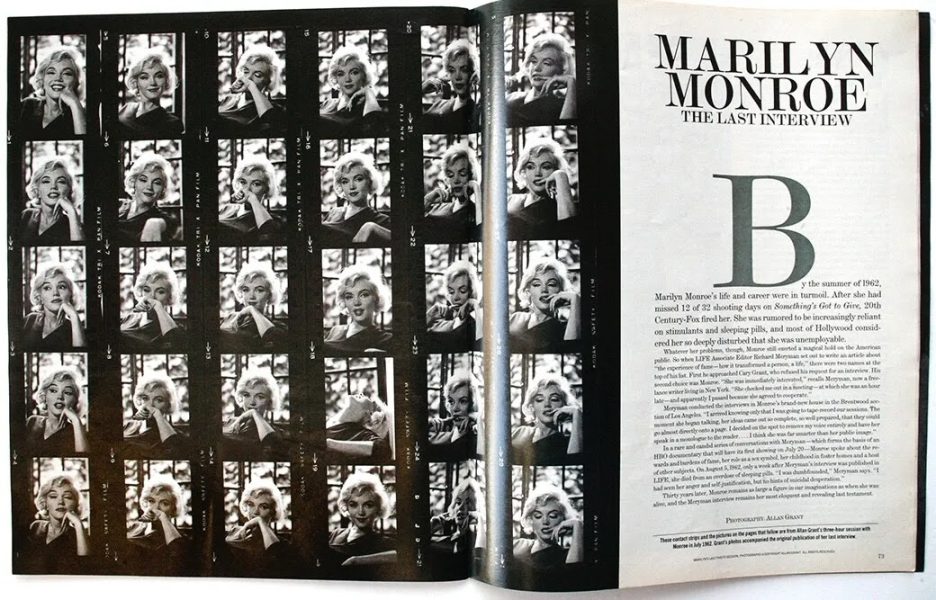

The cultural touchpoints in the exhibition are manifold. One month before she overdosed on barbiturates, Marilyn Monroe sat perched on a chair for one of her last photo shoots in a dark blouse and heels. Alert and expressive, she seems here vibrant and alive—no signs of anxiety or dread that might hint at her impending death.

MoMA has long hosted installations centered on stars. In Face Value, the sparkly black floors and navy-painted walls evoke Old Hollywood. When deciding which photos to select from 16,500 in the museum’s repository, Magliozzi searched for those that were particularly beautiful or contained unique visual motifs like shadows. “The lighting and the spacing between the photographs control your experience,” he adds.

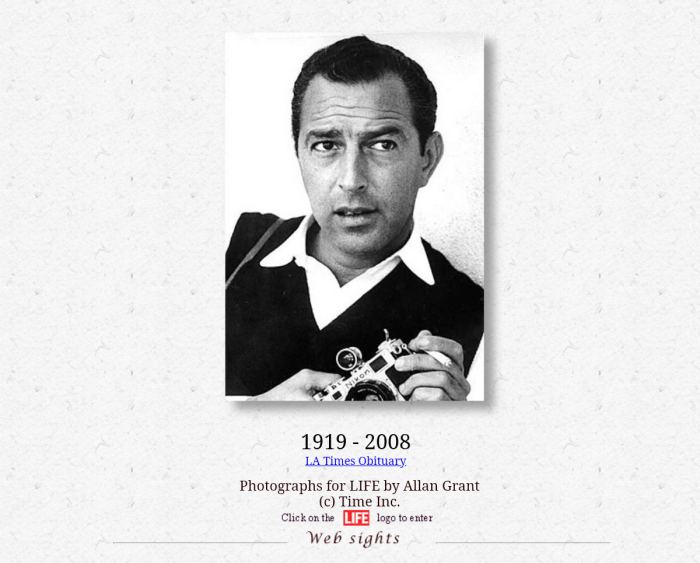

Allan Grant photographed Marilyn in her final home at Fifth Helena Drive in Brentwood, Los Angeles. Both images were published in the August 3, 1962 edition of LIFE, and her home-help Eunice Murray would recall seeing the magazine on Saturday, August 4 – which sadly turned out to be Marilyn’s last day alive.

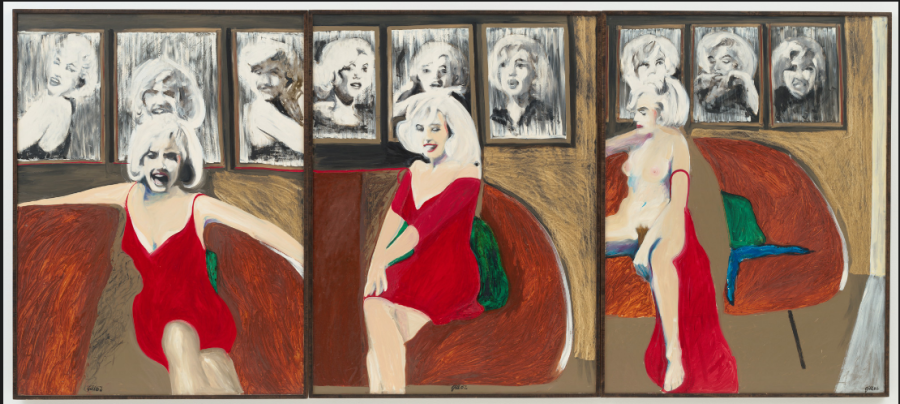

Grant’s photos inspired one of the original American pop artists, James Francis Gill, to paint his ‘Marilyn Triptych’ in the weeks after her death. It was acquired by MoMA for their permanent collection in November 1962.

Marilyn’s final interview with journalist Richard Meryman was reprinted on the 30th anniversary of her death, in LIFE‘s August 1992 issue.

Allan Grant would later describe his encounter with Marilyn in an essay for his personal website.

“On July 7th, 1962 I had arrived at her Brentwood home for what turned out to be her very last photo session. It was a little over three weeks before she died.

I arrived at 1:45 pm. Marilyn, I was told, was on the telephone and would be ready in a few minutes. Pat Newcomb, Marilyn’s publicist and close friend, introduced me to Allan Snyder, Marilyn’s make-up man and Eunice Murray, her live-in housekeeper and companion. Marilyn’s hairdresser was in another room doing her hair. I set up my lights and loaded my cameras and waited. Twenty minutes later she showed up, in a bathrobe and, not surprisingly, with a glass of champagne. (Most movie stars would have a drink or two before a LIFE cover shoot.) Marilyn was still far from ready and I had to get my film on an airplane in three hours. I was getting nervous.

She offered me some champagne which I gladly accepted. It helped. She asked me what she should wear for the photographs. Told her to dress very casually. I told her what I had in mind and she should make her own choices as to what would make her comfortable. She left with her make-up man and hairdresser. About twenty-five minutes later she appeared in tight fitting capri pants and a dark v-neck sweater. There was nothing about her that reminded me of the lush, laughing, Marilyn Monroe of the big screen. To me she seemed somewhat thinner and much more fragile than I expected, and I detected a sadness about her. She had become the Marilyn they asked for.

I had spotted an interesting looking antique chair sitting in the comer of the dining room and moved it in front of a sunlit window to catch the light which would be coming from behind her. I sat her down and explained to her what we were trying to do was to illustrate the interview she had done two weeks before which she had approved and was scheduled to be published on August 3rd. LIFE also agreed to give her the right to disapprove of any of the photographs that I had shot.

I remembered some of the text in the article and asked her to talk about her childhood. As she talked one minute she was the pale schoolgirl, frightened and unsure; then she became cheerful, seductive and glamorous. ‘Tell me about fame,’ I asked. There was a vulnerability about her which was quite touching. But, somehow her sexuality always managed to cut through the haze of her personality.

We took a break to reload my cameras and relax. At that point she grabbed my hand and took me on a quick tour of her recently purchased house.

When she first saw the house in Brentwood, Marilyn liked it immediately. She liked the simplicity and the privacy of the property as well as the fact that it was not new but had been lived in by a family with small children. It was a small but charming Spanish style house that was built in the nineteen twenties. The family who lived there decided they needed a bigger home where their children could grow.

‘I didn’t want a house in Beverly Hills, and I didn’t want a “Movie Star’s Palace”‘, she said, ‘I just wanted a small house for me and my friends.’

Her privacy was very important to her so she had her neighbours carefully checked out – it was a dead end street with two other houses on the property. She discovered that one of the neighbors was a UCLA professor; she felt better about it.

When Marilyn signed the papers for the purchase of the house she was legally alone. Yet, for her, it was the beginning of a new dream. She wanted some changes made as soon as possible. New cabinets in the kitchen, new fixtures in the bathroom new paint on the walls and hand made furniture from Mexico.

Later on, since there would be people working on the house, she had replaced her private unlisted phone number with a phone number from the West Los Angeles police department. She knew that the going rate for her private number was a substantial sum of money. Any plumber or carpenter might see it and pass it on to someone. who would make an obscene phone call and find himself talking to a cop. The thought tickled her.

Although each room she showed me was devoid of furniture, she described each piece in detail as if it was already placed in the room. She told me of her interest in designing furniture and of her trips to Mexico where the furniture was being made. It was three weeks before her tragic death, I’m sure suicide was the furthest thing from her mind.

In the LIFE article, an outspoken and gutsy Marilyn talked angrily about the Major studios, stardom and fame. Fame, for all it had brought her was not the most important thing in her life, she concluded: ‘I now live in my work and in relationships with a few people I can count on … Fame will go by and, so long I’ve had you, fame. If it goes by, I’ve always known it was fickle. So at least it is something I have experienced, but that’s not where I live.'”