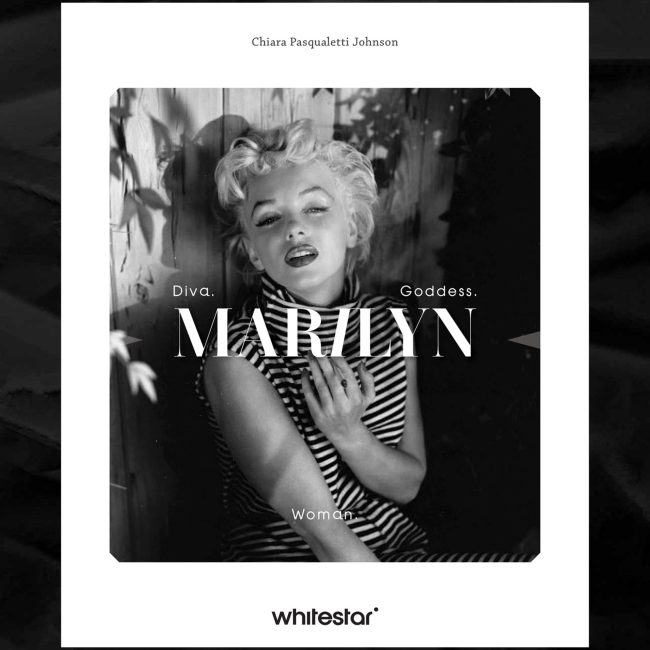

Chiara Pasqualetti Johnson’s pictorial biography, Marilyn Monroe: Diva. Woman. Goddess is published this week in English, Italian, French and German editions. Featuring around 160 photos within its 224 pages, it is part of a series from Italian publisher White Star, profiling famous women like Jacqueline Kennedy, Coco Chanel, and Frida Kahlo.

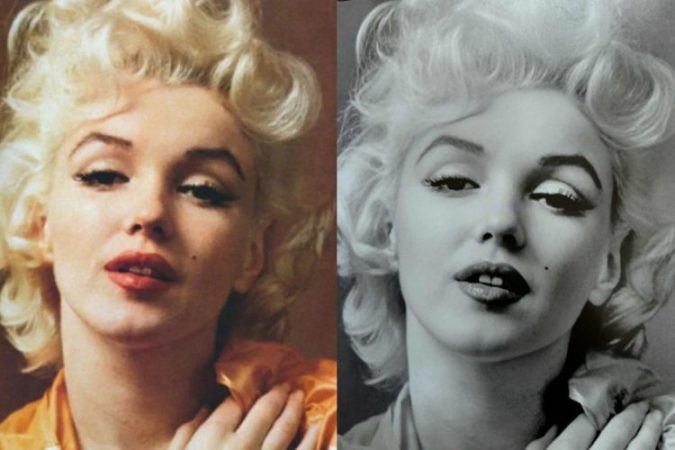

The cover image was shot by Stirling Henry Nahum, a British society portraitist. Known professionally as ‘Baron’, he photographed Marilyn while visiting Hollywood in 1954. (Inside, a colour photo from the same sitting shown above is wrongly attributed to Ted Baron – a name he never used.)

Unfortunately, the blurb suggests a rather gossipy take on Marilyn, with its focus on the men in her life seemingly contradicting the female-powered remit of this series.

“Timeless, iconic, and a universal sex symbol, Marilyn Monroe remains one of the most beloved divas of all time.

The actress was able to, simultaneously, exude an air of seduction and ‘girl-next-door’, all while conquering Hollywood with her pin-up figure and platinum blonde ‘do. The celebrity famously won the heart of baseball champion, Joe DiMaggio, as well as that of U.S. President John Fitzgerald Kennedy.

But beyond the persona, Norma Jeane was a rich and complex human being the survivor of childhood trauma and an adult in need of constant affection.

This engaging, in-depth, and illustrated biography reveals the many faces of both the actress, and the woman behind the legend. Dive in and be filled with awe!”

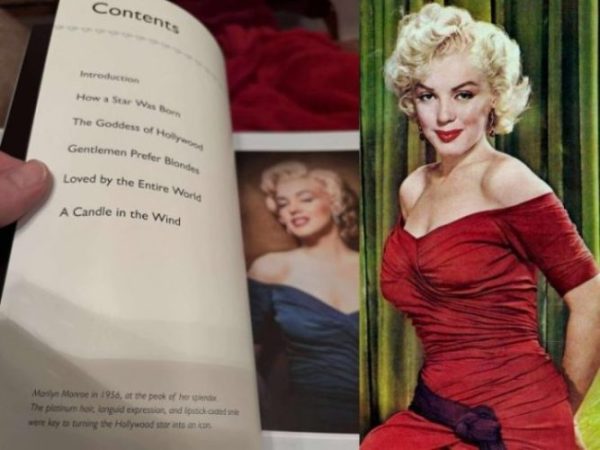

The contents page (above left) includes a colourised version of a black-and-white photo dated to 1956. In fact, it was shot by Gene Kornman in 1952; and Marilyn’s Oleg Cassini dress – worn to the premiere of Monkey Business that September – was red, not blue, as shown in Franck Livia’s colour images from the same period (above right.)

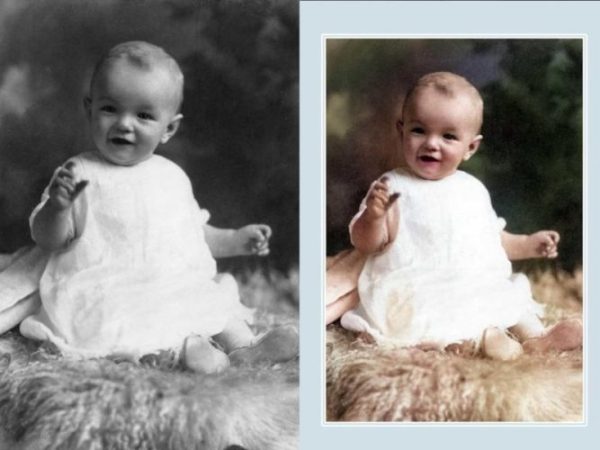

Born in 1926, Norma Jeane Baker grew up to become one of the world’s most photographed women. Many of those images were shot in black-and-white, and some have been colourised to varying effect. A slightly later photo is over-filtered (see below.)

“‘Every child needs a father,’ sang Marilyn Monroe in one of her first roles, that of a dancer in search of true love in Blonde Orchid …” Thus begins the first chapter, and it may confuse some readers. Orchidea Bionda was the Italian title for Ladies of the Chorus (1948), and the lyric Marilyn sang was rich with innuendo: ‘Every baby needs a da-da-daddy …’

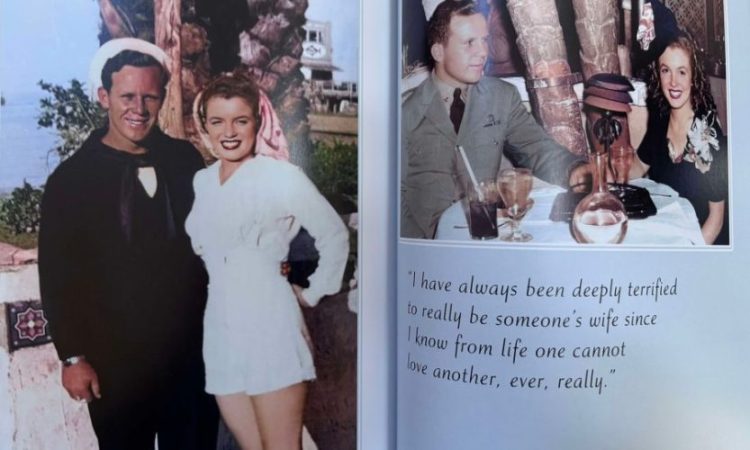

These colourised images of Norma Jeane with her first husband look overcooked, especially when compared to unaltered photos from the same era. (The accompanying quote derives from a note written many years later.)

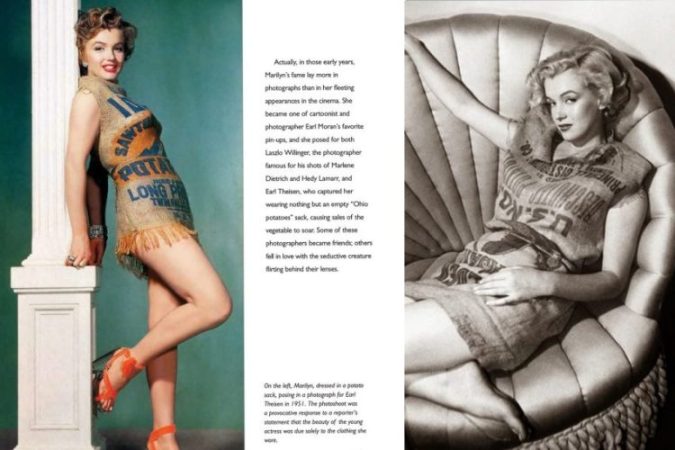

Gene Kornman’s 1952 shot of Marilyn in her famous potato sack (above left) is mistakenly attributed to Earl Thiesen. This is another common error, as Marilyn had struck a similar pose for Thiesen in 1951 (at right.)

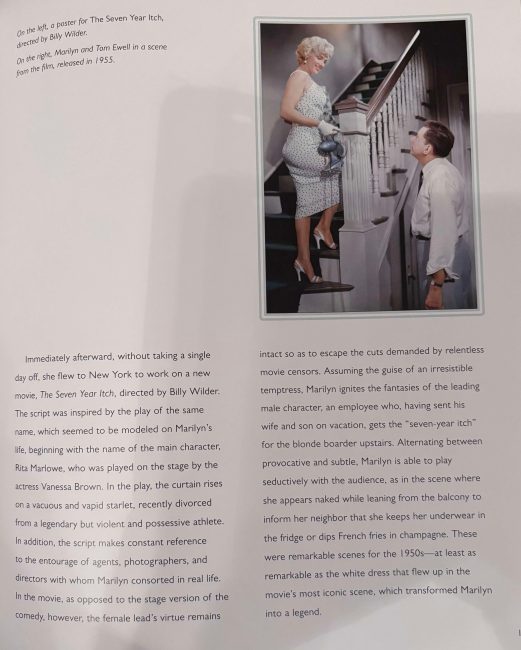

In a passage about The Seven Year Itch (1955), the author confuses Marilyn’s character – known only as The Girl – with Rita Marlowe, the starlet played by Jayne Mansfield in 1957’s Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? Both were based on plays by George Axelrod, but while Marilyn was rumoured to have partly inspired his later creation, the plotlines did not coalesce.

A 1954 photo showing Marilyn in the same costume she later wore for Bus Stop (1956) is one of many images restored by the Milton Greene estate – but in this book, the colour is further embellished. And below, a colour portrait shot by Greene’s assistant Hal Berg in 1955 has been greyscaled, with the texture of Marilyn’s skin lost amid the monochrome sheen.

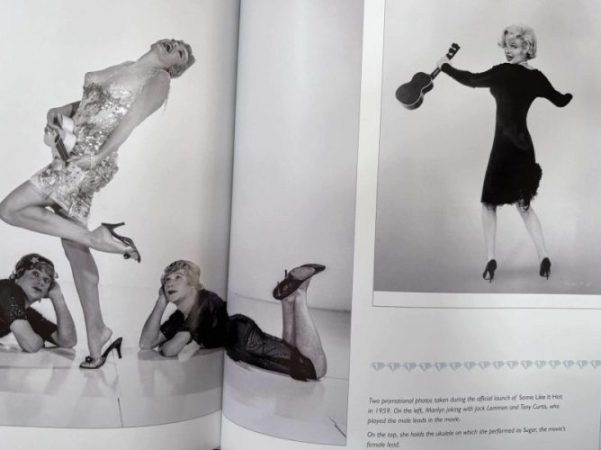

A publicity photo for Some Like It Hot (below, at left) misidentifies the model with Jack Lemmon and Tony Curtis as Marilyn. In fact, Sandra Warner – who also had a small part in the film – was a stand-in for Monroe, then unavailable.

This was routine in Hollywood at the time, with the star superimposed onto the stand-in during the editing process. However, Richard Avedon’s photo of Marilyn in another costume (above right) shows the difference in their figures.

Although not used in the book, these variant images enable a closer comparison. Sandra has often been mislabelled, but photo libraries like Getty have named her as Marilyn’s stand-in for the shoot.

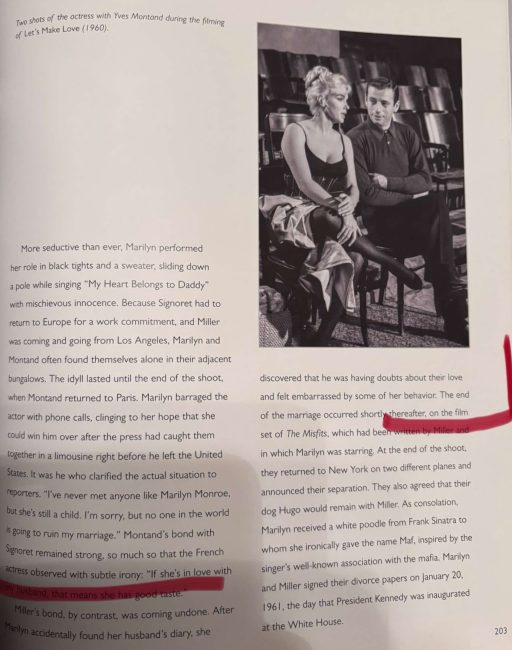

A more serious factual error occurs in a passage regarding Marilyn’s affair with Yves Montand, her co-star in Let’s Make Love (1960.) The author claims that Marilyn was devastated to read pages from Miller’s diary in which he admitted to having ‘doubts about their love and felt embarrassed by some of her behaviour.’ However, this marital crisis happened four years earlier, when Marilyn was shooting The Prince and the Showgirl in England.

Perhaps the worst photographic mishap in this book is the greyscaling of a gorgeous 1961 portrait by Douglas Kirkland, with its soft colours rendered cold and metallic, and Marilyn’s face barely recognisable.

The book is peppered with quotes from Marilyn, some requiring further context. Shown above are two examples of reported speech. The quote at left comes from a conversation with Henry Hathaway, director of Niagara (1953), who met Marilyn again on the Paramount lot in 1960, as she finished work on The Misfits. Hathaway retold the story in an interview for John Kobal’s People Will Talk (1985.)

The other quote is from a conversation with Dr. Richard Cottrell, who treated Marilyn at the Polyclinic Hospital while she recovered from gallbladder surgery in 1961. Cottrell shared his memories with a Ladies Home Companion reporter in 1965, three years after Marilyn died. The original wording has been abbreviated: ‘Look at them up there. Look at the stars. They are all up there shining so brightly, but each one must be so very much alone.’

Other supposed ‘Monroeisms’, veering from sentimental to asinine, cannot be traced to primary sources, and most likely germinated on social media (see below.) Another online misquote is blended with a paraphrasing of Julia Roberts’ famous line from the hit rom-com, Notting Hill (1999): ‘I’m also just a girl, standing in front of a boy, asking him to love her.’

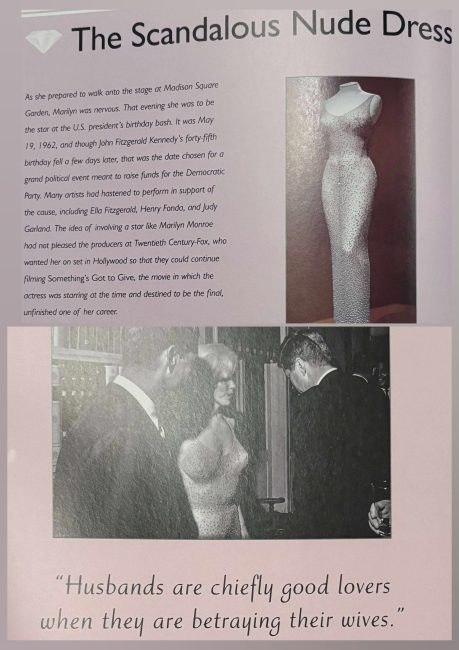

‘It is impossible to disentangle the truth from fiction in any reconstruction of the affair between the movie star and the U.S. president,’ the author writes. ‘They held their rendezvous in the presidential apartments at the Carlyle Hotel in New York or Santa Monica or at the country estate of Peter Lawford and his wife, Patricia, Kennedy’s sister.’

In fact, their only verifiable encounter was at the Madison Square Garden gala when Marilyn sang famously ‘Happy Birthday Mr President.’ They were photographed together at an after-party, before Marilyn left with her ex-father-in-law, Isidore Miller. The author also claims that Marilyn gave the president a gold Rolex watch (sold at auction for $120,000 in 2005) on which she had engraved the words: ‘To Jack, with love as always from Marilyn.’ However, a serial number is said to indicate that it was manufactured in 1965, when neither Monroe or Kennedy were still living.

‘News that she had begun dating Bobby Kennedy […] had already leaked within the ranks of the president’s entourage,’ the author continues. ‘Although there’s no evidence that the two did have an affair, they definitely became friends.’ In fact, she met Bobby twice at the Lawfords’ beachfront home in Santa Monica, and not at a ‘country estate.’

The Attorney General briefly visited Marilyn’s new home with Peter Lawford, and she telephoned him several times at the Justice Department, although he wasn’t always available. Overall, the evidence suggests a friendly acquaintance that was probably more significant to Marilyn than Bobby.

When recounting events leading to Marilyn’s death, the author alludes to conspiracy theories without drawing any solid verdict. Nonetheless, she writes frankly about Marilyn’s long struggle with mental illness and drug abuse.

“Painfully aware of her fragility, Marilyn had been seeing psychiatrists for some time, a rampant practice among the affluent in California. Clearly, she needed some kind of help, but at that time it was not easy to distinguish professionals from self-proclaimed gurus who projected confidence and advertised their competence with the right rhetoric. While living in New York, Marilyn had spent several months working with Dr. Margaret Hohenberg, who pushed her to deal with her childhood traumas. This type of therapy threw the actress’s life out of whack, without leading to any positive results. Two years later, when she again began searching for an analyst, she turned to Marianne Kris … In 1960, she met Dr. Ralph Greenson, the last of an endless series of specialists to test their questionable psychoanalytical methods on the star …. Seeing Marilyn in his office nearly every day, he prescribed her massive doses of pills that, instead of helping her, made her sink deeper into hell.”

However, Marilyn had been misusing sleeping pills at least five years when she became Greenson’s patient, and was narrowly saved from overdoses on multiple occasions. Some of his more unorthodox strategies, such as inviting Marilyn into his family home, were desperate efforts to alleviate her extreme loneliness. After a traumatic experience at the Payne Whitney Clinic, she refused to consider institutional care; and as she often expressed suicidal thoughts, Greenson hired an assistant, Eunice Murray, to care for her at home.

“In the middle of the night, friends would receive frantic calls from her, begging them to throw something over their pajamas and come immediately to console her. Among these were women and men just as depressed as she was, who also had fallen into a downward spiral thanks to alcohol and drugs. It was thus that the formerly health-conscious young woman, who had once kept weights under her couch to stay in shape, crossed yet another threshold, that leading to Hollywood’s world of addiction … By this point of her life, Marilyn was totally dependent on them; sleep had become practically impossible without the help of a few pills.”

Marilyn Monroe: Diva. Goddess. Woman is not the only pictorial biography marred by factual errors, but its digital manipulation of vintage photographs – which for many readers will be its main attraction – reduces some to mediocrity. As Chiara Pasqualetti Johnson proposed in her introduction, this book could have been so much better.

“On these pages, truth and fiction intertwine in a complex jumble that Marilyn herself made extremely difficult to unravel as she sought the path that led to success. Forever suspended between ambition and modesty, she reflected on the dangers of fame in her final interview. ‘It’s nice to be included in people’s fantasies, but you also like to be accepted for your own sake,’ she noted. But who, in actual reality, was Marilyn Monroe? To find her, I tried to look beyond my biases and force myself to tell her story nonjudgmentally. I ask all of you to do the same as you leaf through this book. To catch a glimpse of the real Marilyn, you need to set aside the image of both the goddess and the star and allow yourself to be surprised by the woman who she was. Intelligent, determined, exceptionally talented, and endowed with an extraordinary sense of humour. A restless, independent, fragile, and mysterious soul. A myth for all time to come.”