While documenting the recent Merry, Merry Marilyn auction, I found myself reflecting on how often her image has been defined by the male gaze. In her lifetime, she became a globally renowned sex symbol and was photographed mostly by men. And after her death, she was eulogised by artistic figures like Andy Warhol and Norman Mailer.

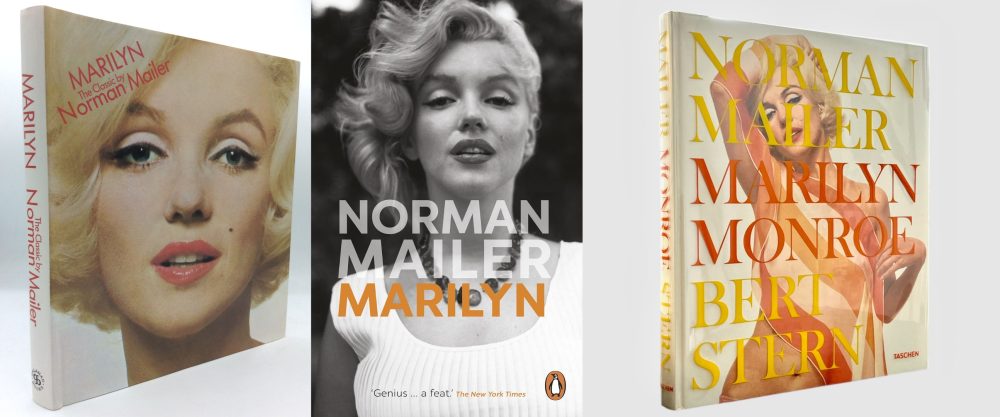

Whereas Warhol arguably brought a queer perspective to Marilyn’s posthumous legacy, Mailer veered closer to the Playboy aesthetic, albeit with a literary flair. But he didn’t work alone, as his 1973 bestseller, Marilyn, was produced in collaboration with one of her last photographers, Lawrence Schiller. (A first-edition hardback copy, signed by both men, was sold at Julien’s Auctions this week.)

This controversial, if visually stunning tome – described by Mailer as a ‘factoid biography’ – helped fuel the fire of conspiracy theories about Marilyn and the Kennedys. It was also the beginning of a lengthy and volatile collaboration, explored by David Margolick in ‘The Oddest Couple in American Literature,’ a three-part series for the digital magazine, Airmail.

If you don’t have a subscription, the second part – covering the Marilyn project – has been posted in full by James Grissom here.

“Dealing with Lawrence Schiller—improbable, inescapable, impossible to define—can be exhausting, as can writing about him … For no one had ever lived a life like Schiller, who, as a photographer, book packager, filmmaker, and indefatigable operator, leapfrogged from celebrity to celebrity, saga to saga, scandal to scandal, attaching himself to everyone from Lee Harvey Oswald to Marilyn Monroe to Charles Manson to Patty Hearst to Norman Mailer, with whom he had—‘enjoyed’ wouldn’t be quite right—the most bizarre and productive literary collaboration ever.

Lawrence Schiller was born on December 28, 1936, in Brooklyn, where Mailer, 13 at the time, had lived since he was 5 … In 1942 the Schillers moved to San Diego, where Schiller’s father ran a camera store. It was there that Schiller got his first lessons in photography and salesmanship … In late 1953, when Schiller was 16, Jacob Deschin, the influential photography columnist, spotted the blend of talent, instinct, eagerness, ambition, and anxiety that propelled him … Over the next 15 years or so, it felt as if the indefatigable Schiller—one reporter called him ‘possibly the least still photographer of all time’—shot just about everybody …

Schiller captured Pat Nixon crying as her husband conceded to J.F.K.; Spencer Tracy and Jimmy Stewart at Clark Gable’s funeral; and a grief-stricken Joe DiMaggio, standing alongside his son in his Marine regalia, at Monroe’s … But he eventually tired of photography—‘different heads on the same bodies,’ he called it—and aspired to more: to ferret out, then tell, then sell the stories other people told him. And to put together his own books, starting with Marilyn: A Biography.

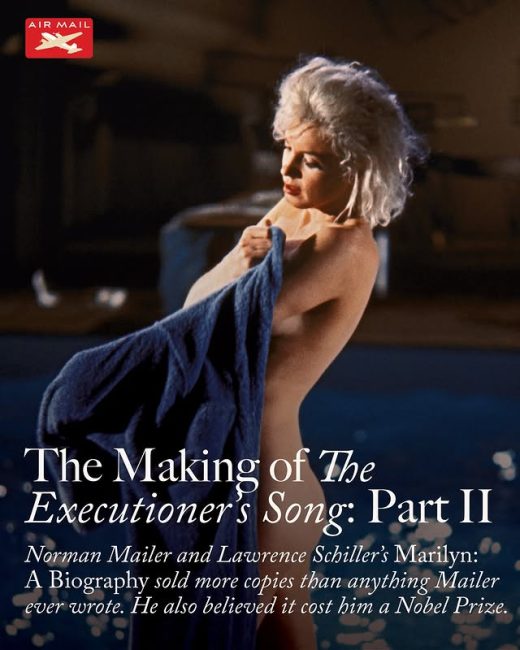

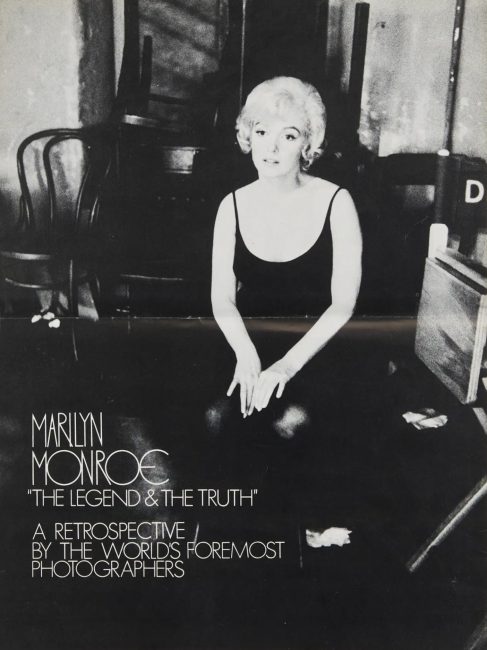

It began with an exhibition of photographs of the actress—taken by, among others, Richard Avedon, Cecil Beaton, Ernst Haas, Milton Greene, Arnold Newman, Bert Stern, and Schiller—that Schiller had assembled for a Los Angeles gallery in 1972 to mark the 10th anniversary of her death. He’d then set out to turn the collection into a book, one that would be, as he liked to say, as ‘lovable, huggable, and fuckable’ as Monroe herself.

As Schiller envisioned it, the text accompanying the pictures would be strictly secondary … In his mind, potential authors were interchangeable; when he first took the idea to Random House (which passed), he suggested Pauline Kael or Rex Reed, whom he’d sort of heard of but never read. But by the time he reached Grosset & Dunlap, which ultimately bought the book, he was aiming higher. ‘Get me Gloria Steinem, get me Norman Mailer!’ he says he told them.

Schiller, of course, knew next to nothing about Mailer either; to him, he was just a guy who shouted louder than anyone else, got into fights, and drank too much. ‘I just threw out the name,’ he said. And damned if, in November 1972, Grosset didn’t promptly go out and sign Mailer up.

Schiller was elated: Mailer’s very involvement, whatever the hell he wrote, would guarantee the covers of Time and Life. Here, too, Schiller’s account is disputed—in this case by Robert Markel, the Grosset editor who’d corralled Mailer, then handled the book. Schiller strutted around town as if ‘he had invented Norman Mailer,’ Markel later said … Schiller, Markel said, took his accusation in stride: ‘He would laugh. He was impervious to insult.’

The publisher gave Mailer $50,000 plus royalties for a 15,000-word essay on Monroe, which he’d have three months to write. (That was also what Schiller would be getting and what the photographers would split among themselves.) Strapped as always—five marriages and seven children had left him with, as he once put it, ‘a financial nut larger than [my] head’—Mailer grabbed the dough, even though, whether or not he realised it, under the contract Schiller would be his boss.

During their first meeting, Schiller laid out the pictures on the floor of a room in Mailer’s house in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. Far from the ogre he’d been anticipating—‘I expected somebody almost like the Hulk or something,’ he says—he found Mailer to be soft-spoken, courteous, and thoughtful. Schiller was thrilled, even proud. ‘He thought this was a wonderful deal he was pulling off,’ Markel recalled. ‘It was no longer just grovelling around in the Hollywood Hills; he’d hit it in New York, big.’ Mailer’s first impressions of Schiller weren’t so favourable. To him, Schiller was an operator … ‘very obviously a man on the make,’ while he, having become a literary prodigy at 25, was already a made man.

Like so many men of his generation, Mailer had long had a thing for Monroe; he was still steamed at Arthur Miller for not inviting him to stop by the couple’s Connecticut home, even though he lived just down the road. Mailer quickly became ‘intoxicated’ with the project, he said, and a good thing, too, given the short deadline, which accounted for his lifting liberally from two prior Monroe biographies; the plagiarism charges that inevitably ensued necessitated payoffs to both authors. But after barely a month, Mailer bragged to Markel that he’d completed the first 65,000 words of a 25,000-word project—and he still hadn’t gotten to Miller!

To Schiller’s horror, Mailer soon tendered an essay of 105,000 words, one that threatened to blow up the layout of the book. More alarming even than Mailer’s prolixity was his convoluted and utterly unsubstantiated speculation about Monroe’s alleged dalliances with former attorney general Robert Kennedy … To Schiller, the Bobby Kennedy business was not only nonsensical but, far worse, distracting—by taking the focus off Marilyn—and even dangerous, threatening to turn off the folks at Time and Life. ‘You are gonna fuckin’ ruin the book if you let Mailer put this Bobby Kennedy shit in,’ he warned the publisher.

Mailer made things worse through his sloppy—or even nonexistent—reporting, failing to interview the one person who could have corroborated his cockamamie theory: Monroe’s maid, Eunice Murray, who was with her the last night of her life. (He’d been told, he said, that Murray had died ‘under violent circumstances’ in Germany; in fact, she was alive and well and listed in the local phone book.)

It was, Schiller quickly realised, a pattern with Mailer, who’d spent more time watching Monroe’s movies than talking to people who’d known her, including Joe DiMaggio. Through the celebrity lawyer Melvin Belli, Schiller had wangled an interview with the notoriously reticent slugger, but Mailer hadn’t talked to him either because, as he later explained, Joltin’ Joe was ‘renowned for saying very little’ to reporters and he’d ‘just lose the comfort of being able to write about him without owing any favor for the interview.’ ‘Norman wasn’t one for researching,’ Schiller says.

When it came right down to it, the two had fundamentally opposed ambitions for the book. All Schiller wanted from him, Mailer complained, ‘was some nice grey matter’ to run between the glitzy photographs. ‘I didn’t give a goddamn about all those fancy publicity shots,’ Mailer later said … As if that weren’t enough, there was also Schiller’s decision to leave Mailer’s name off the cover, which, as he envisioned it, would consist simply of a photograph of Marilyn with no words at all …

So as Mailer later put it, he and Schiller had quickly gone from ‘looking at the other and saying, “Who the hell are you?,” to being absolutely adversaries.’ To iron things out, Grosset & Dunlap pushed for a summit meeting between the two; with both in transit, it had to be held in the United Airlines Friendship Lounge at Kennedy Airport. There, Schiller laid out the photographs as they’d appear in the book, and Mailer tried moving them around—essentially redesigning the whole thing …

Schiller threw Mailer a few crumbs, agreeing to run some of the snapshots Mailer had pushed for, in the margins. ‘But you’re fucking up the book,’ he says he told him. ‘And he’s saying, “Don’t tell me. I know more about book publishing. You’ve never published a book before.” He said something like, “Larry, you don’t know a damn thing about laying out books.” And I said, “Well, what do you fuckin’ know about Marilyn Monroe?” He said, “What do you know?” And I said something like, “At least I fucked her.”’ (Whether this is another ‘Schiller legend’ is impossible to know.)

Schiller says he and Mailer ‘almost’ came to blows. Toward the end of the meeting—and much to Markel’s consternation—Mailer and Schiller went outside. But rather than duke it out, Schiller simply took Mailer’s picture—for what, he didn’t say—capturing him at his seething, suspicious best … By that point, Markel’s goal was simply to keep a lid on things until Schiller boarded his flight to California. But watching Mailer watch Schiller that day, he spotted something else, different and surprising: appreciation. ‘Norman is really quite patient with this character and sort of amused with him,’ Markel recalled … ‘He saw something of himself in this guy.’

‘I had no idea of what he really thought of me after that meeting,’ Schiller says. ‘And, quite honestly, I didn’t care. I was on a train of success with the book and nothing was going to deter me.’ In fact, he wound up printing nearly everything Mailer wrote, including all that ‘Bobby Kennedy shit.’ How could he not? ‘I’ve got Norman Mailer. I’m gonna have to live with him,’ he came to realise.

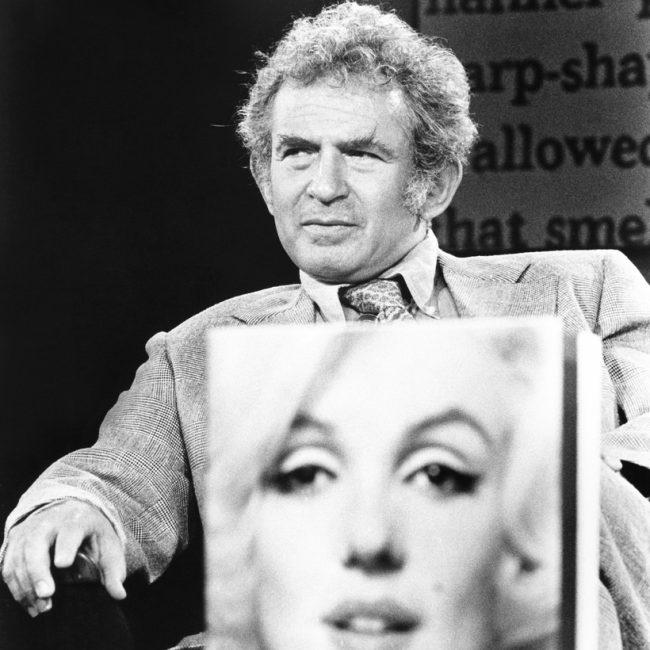

All along, Schiller had told people the book would land on the cover of Time, and it did. He also said he and his team would design that cover themselves, something the magazine had never let anyone do, and they pulled that off as well. It featured a collage of a smiling and seductive Marilyn (in living colour, taken by Bert Stern), standing above a black-and-white, glowering Mailer (the photo Schiller took outside the Friendship Lounge), tousling his hair. Schiller knew it would infuriate Mailer, but didn’t care. ‘Norman Mailer had served his purpose,’ he explains. ‘And he’d fucked me over with this Bobby Kennedy shit.’ By having been made to look silly, Mailer believed that photo cost him a Nobel Prize…

Besides landing the covers of Time and Life, Schiller also got the book on 60 Minutes, though not with the results he’d imagined; ‘Monroe, Mailer, and the Fast Buck,’ the segment was entitled. Schiller watched in horror as Mike Wallace eviscerated the unprepared, overheated, and stammering Mailer, who admitted to having taken the job because he ‘needed some money very badly,’ adding for good measure that he didn’t ‘believe in fact-gathering.’ Wallace also produced the missing Eunice Murray, who laughed off Mailer’s Bobby Kennedy fantasies. ‘Norman,’ Schiller says, ‘was terrible on a lot of things in his life.’

By Schiller’s calculations, Mailer’s dismal performance cut book sales in half. But he’d Mailer-proofed the book in advance through sales to book clubs, foreign publishers, and magazines. Marilyn wound up selling an extraordinary 400,000 copies worldwide, earning Mailer half a million dollars despite himself. An unapologetic Mailer later claimed it was ‘among my better books,’ despite having been written in three months for ‘a couple of psychotic liars.’ But never, he vowed, would he work with Schiller again.

Schiller wasn’t much happier with Mailer, but hedged his bets. Any frustration he’d felt with Mailer felt picayune next to the gift Mailer had given him. ‘It was an incredible education. Matching myself against Norman. Matching my gut with his intelligence.’ So the two stayed in wary proximity … ‘There was this love-hate for a while,’ Schiller recalls of their relationship. ‘We weren’t talking to one another. But we were talking.’”