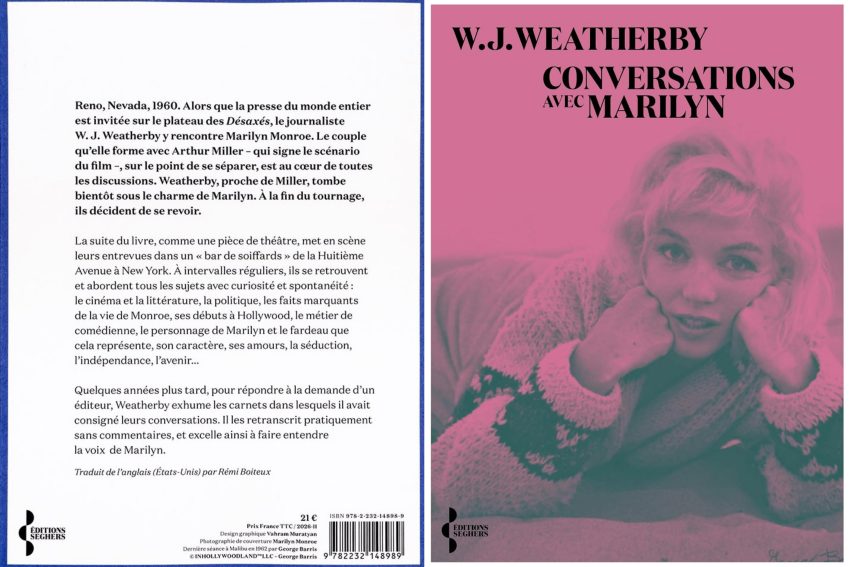

Fifty years after its original release, Conversations With Marilyn has been published in France for the first time.

“Reno, Nevada, 1960. While the world’s press is gathered on the set of The Misfits, journalist W. J. Weatherby meets Marilyn Monroe. Her relationship with Arthur Miller—who wrote the screenplay—is on the verge of breaking up and is the main topic of conversation. Weatherby, close to Miller, soon falls under Marilyn’s spell. At the end of filming, they decide to meet again.

The rest of the book, like a play, depicts their encounters in a dive bar on Eighth Avenue in New York City. At regular intervals, they met and discussed all sorts of topics with curiosity and spontaneity: reflections on literature, theatre, and film; the defining moments of Monroe’s life—her childhood, Hollywood, the ‘character’ she embodied and the burden it represented for her—sexuality, marriage, independence…

A few years later, at the request of a publisher, Weatherby unearthed the notebooks in which he had recorded their conversations. He transcribed them almost without commentary, and thus excelled at conveying Marilyn’s ‘voice.'”

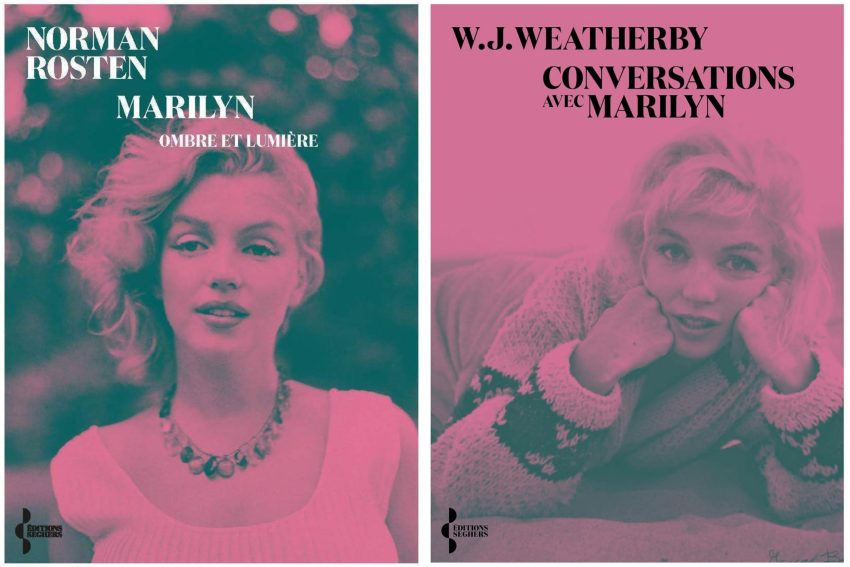

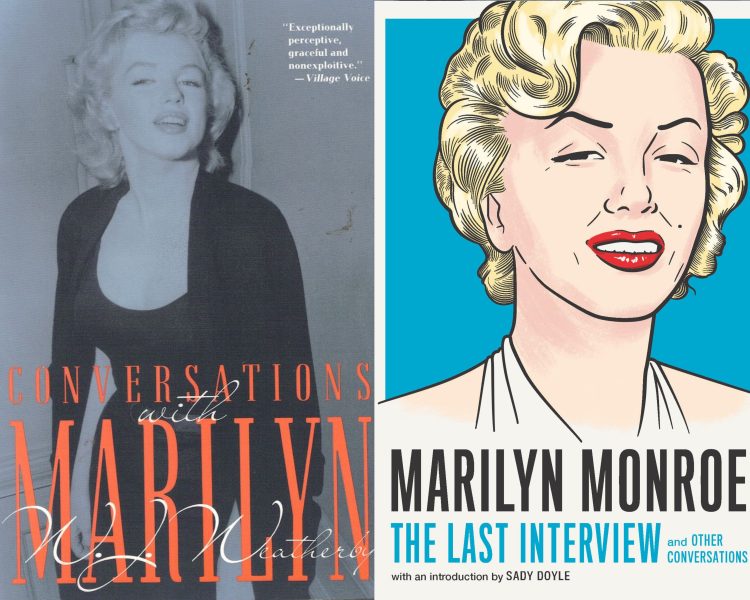

Conversations With Marilyn is available in paperback and digital formats. The cover artwork uses a photo of Marilyn in 1962 by George Barris, with the original image reproduced inside, alongside a new French translation by Rémi Boiteux.

Publisher Editions Seghers previously reissued Norman Rosten’s memoir, Marilyn: An Untold Story, in 2022.

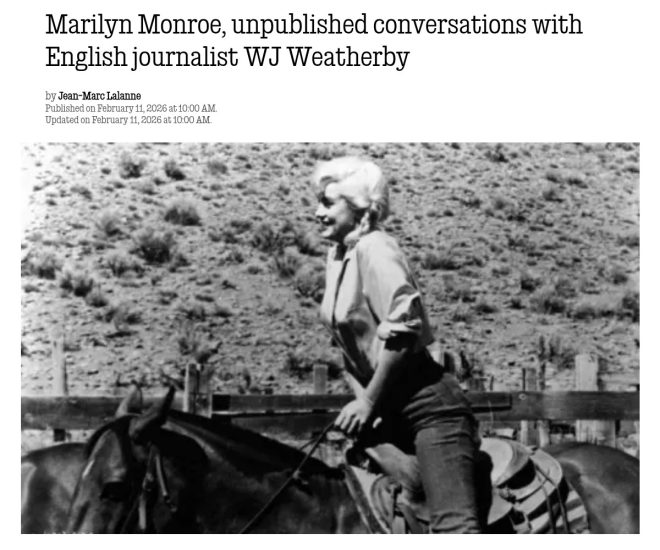

Earlier this week, Weatherby’s memoir earned a glowing review from Jean-Marc Lalanne for Les Inrockuptibles.

“Against the mountainous backdrop of Nevada, hounded by paparazzi and harassed by gossip columns, Marilyn is initially evasive. But, intrigued by the journalist’s reluctance to make the first move, she eventually approaches him. Weatherby vividly portrays how the star oscillates between surrender and mistrust, seduction and withdrawal. He masterfully recreates the backdrop of the tumultuous filming of The Misfits, the anxiety of Arthur Miller, who wrote the film and knows his marriage to Marilyn is nearing its end, and the Nixon-Kennedy presidential contest, whose twists and turns the team eagerly follows …

After filming wrapped, the journalist and the star might never have seen each other again. But for reasons Weatherby still wonders about, Marilyn regularly contacted him in the months that followed. They both lived in New York. She repeatedly expressed a desire to have drinks with him. They met at a decidedly unpretentious bar on 8th Avenue where the star, wearing a headscarf and hidden behind dark glasses, went unnoticed. ‘She could turn her aura on and off at will,’ Weatherby noted, impressed. They quickly agreed that he wouldn’t use these informal conversations to write a story about her (which would have made every newspaper in the world salivate). But he wondered if, while pretending to want these exchanges to remain private, she wasn’t convinced—and even eager—that one day, perhaps much later, he would do something with them. Perhaps write a book.

She confides in him about her separation from Arthur Miller, mentions Simone Signoret and Yves Montand, and talks about her reading. Curious and attentive, she asks him numerous questions: about his work, his life, his relationship with a young African-American woman. At times, she seems to disconnect from the conversation, retreating into her own thoughts, absent from others and perhaps even from herself. To bring her back, he then says her first name (‘Marilyn?’), seeming surprised himself that he can utter that word to the most famous Marilyn in the world, standing incognito just inches away from him.

The book is truly beautiful because it gives the impression of letting us hear a conversation between ghosts. Marilyn, of course, is a ghost, both intimate and spectral, her presence taking on the unreal quality of an apparition. But Weatherby, too, succeeds in creating a striking self-portrait of a great interviewer as a ghost, whose life consisted of living in the shadow of the illustrious artists he encountered (James Baldwin, Ernest Hemingway, Marlon Brando, Tennessee Williams …), a semi-unknown figure wandering among idols. The text itself is a revenant, made up of conversations that were meant to be silenced and reach us even though the world they resurrect has sunk into oblivion.”

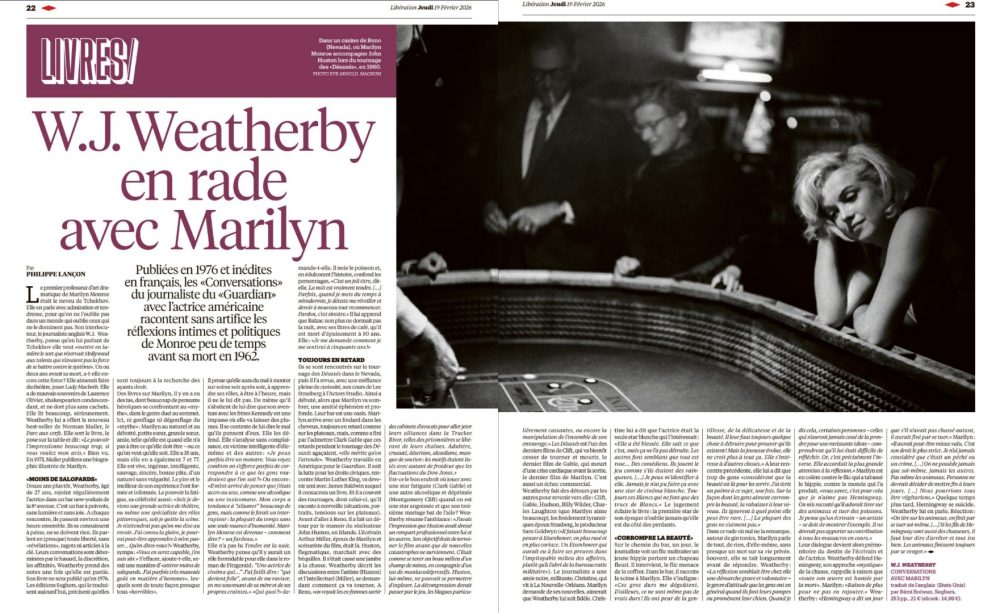

Conversations With Marilyn was also featured in the February 19 edition of the French newspaper, Libération.

While Weatherby’s book was mostly well-received by Monroe fans, some have raised significant doubts. He was listed in Marilyn’s final address book, and although their conversations were not recorded, writing from memory was not uncommon at the time. His account of the Misfits shoot is considered reliable, but the New York meetings with Marilyn are harder to pin down.

After The Misfits wrapped in October 1960, Marilyn returned to her Manhattan apartment. During the summer of 1961, however, she moved back to Los Angeles and apart from a few brief visits to New York, she lived on the West Coast until her death in August 1962.

Weatherby later came to know Robert Slatzer, author of The Curious Death of Marilyn Monroe (1974.) Slatzer made a number of debunked assertions, even claiming that he was secretly married to Marilyn. Many of the conspiracy tropes surrounding her death originated with Slatzer, whom Weatherby mentioned in his book.

For these reasons, the later chapters of Conversations With Marilyn – and especially her alleged comments about the Kennedys – are questionable. It would be interesting to know if Weatherby’s notebooks survived his death in 1992.

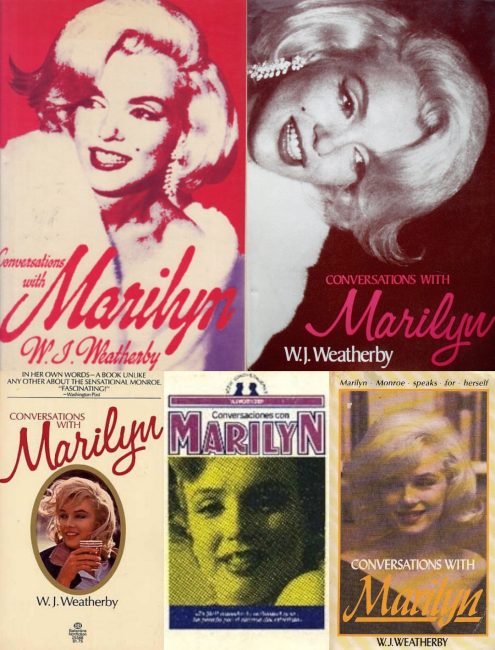

The UK and US editions are now out of print, although extracts were featured in the 2022 anthology, Marilyn Monroe: The Last Interview and Other Conversations. Reasonably priced copies of Conversations With Marilyn (in English) are fairly easy to find at used bookstores, and it is also available via the Internet Archive.

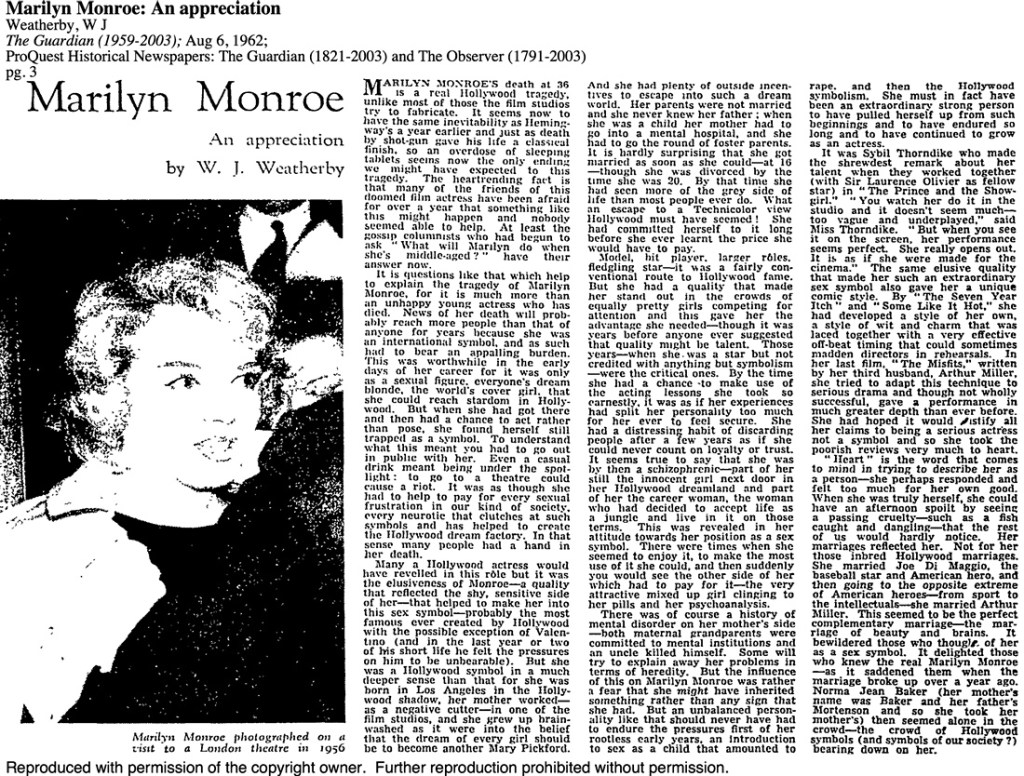

And finally, Weatherby’s earliest tribute to Marilyn was published alongside her obituary (by Alastair Cooke) in The Guardian on August 6, 1962.