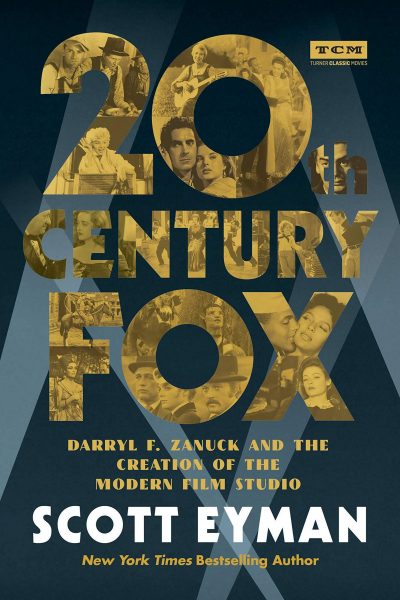

Classic film scholar Scott Eyman’s books include collaborations with Robert Wagner, and a biography of Cary Grant. His latest volume 20th Century Fox: Darryl F. Zanuck and the Creation of the Modern Film Studio, depicts the iconic company in its glamorous heyday, through to the modern blockbuster era. While it’s more a studio story than a star study, Marilyn’s stormy tenure is mentioned, and an image of her waving from a window in the final scene of The Seven Year Itch (1955) can be glimpsed on the cover.

“Zanuck confounded expectations by devising a three-pronged system of colourful entertainment by the masses, involving historical epics … bright, flouncy musicals starring what came to be known as Fox blondes (Betty Grable, Alice Faye, June Haver, Marilyn Monroe); and serious dramas …

In the early 1950s, Fox struck gold with Marilyn Monroe, one of the primary stars of the decade. It was a partnership stunted by the mingled backgrounds of the people involved … As far as Zanuck was concerned, Monroe was a none-too-bright starlet who had unaccountably become a movie star through a fluke of the camera. He simply could not bring himself to fully respect her as an actress or a woman. From Monroe’s point of view, her past history with Zanuck and [Joseph] Schenck only made her more conscious of their lack of respect toward her, producing a toxic combination of insecurity and anger.

Zanuck was also annoyed by her lack of professionalism and her affectations. When Zanuck slotted Monroe in Don’t Bother to Knock, a decent movie directed by Roy Ward Baker, she made what would become her standard request to have her drama coach Natasha Lytess on the set. Zanuck responded with a subtly scathing memo in which he termed her request ‘completely impractical and impossible … You cannot be coached on the sidelines or the result would be a disaster for you …’

It didn’t work. Monroe couldn’t work without a personal crutch. Lytess worked as her on-set drama coach through The Seven Year Itch, after which Monroe replaced her with Paula Strasberg, the wife of Actors Studio head Lee Strasberg.”

Eyman also examines how the emergence of CinemaScope paralleled Marilyn’s rise to fame, plus how the financial woes faced by Fox hastened her untimely demise, and Zanuck’s return after six years in Europe.

“How to Marry a Millionaire, the second CinemaScope picture [on release], made $8 million in rentals, far more than the $5.3 million earned by Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, which also starred Marilyn Monroe but was in standard format … The three CinemaScope Fox released in 1953 jacked up their profits by 13 percent. In 1954, profits rose for the first thirty-nine weeks of the year rose 400 percent … Films using widescreen technology accounted for less than 10 percent of movies in 1953; by 1959 that figure had risen to 40 percent.

On May 28, 1962, [Joseph L.] Mankiewicz called ‘Cut’ on what he thought was the end of the main shooting of Cleopatra. At this point, Fox had spent more than $30 million … Back in Hollywood, Fox had being trying to make a modestly budgeted romantic comedy with Marilyn Monroe and Dean Martin called Something’s Got to Give, one of the more prophetic titles in movie history. Monroe looked luminous, but could not bring herself to show up with any regularity. Finally, Fox cancelled the movie and wrote off a $2 million loss. Shortly afterward, Monroe died from an overdose of sleeping pills.

In 1962, Fox lost $39.8 million after taxes. The mounting debts forced the studio to start divesting. First to go was its entire land holding in Westwood, sold to the Alcoa Aluminium Company. The price for the 334-acre lot was $43 million, with Alcoa promptly leasing back 75 acres to Fox as its core holding. While all of this was going on, Zanuck was finishing The Longest Day. The final cost was $7.75 million … To forestall the throwing away of his dream project, Zanuck announced his candidacy for the chairman of the board. The Longest Day was released as Zanuck wished and returned $17.5 million domestically.

On July 25, 1962, Zanuck was elected chairman … He had no intention of re-upping for his old job, he told [his son] Richard. In fact, he had no intention of going back to Los Angeles, he was going to live in either Paris or New York. Richard Zanuck returned to his father’s suite a few hours later and handed him a piece of paper with one name on it: Richard Zanuck … And just like that, Richard ascended to the job his father had always expected him to have.

On August 31, Darryl Zanuck wrote Joseph Mankiewicz that he wanted to see a first cut of Cleopatra … After seeing Mankiewicz’s rough cut, Zanuck essentially took over … Publicly, Fox said that Cleopatra cost $44 million, but their books actually carried the cost at $42 million. In its first release, Cleopatra returned $26 million in domestic rentals. Eventually, it turned a profit.

Darryl Zanuck’s last interview seems to have taken place in 1975. ‘In the afternoon I start watching TV for a few hours,’ he said. ‘Every time they show something like Eddie Robinson or Marilyn Monroe or Betty Grable or Ty Power or Dick Widmark – the so-called Golden Age of Hollywood – it conjures up memories. I don’t want to sound immodest. People have accused me of being a lot of things. But a lot of that Golden Age of Hollywood – it was of my making.’

On October 29, 1979, he had a heart attack, then a stroke followed by pneumonia. With characteristic will, he struggled on for nearly two months until his death on December 22, 1979, at the age of seventy-seven.”

1 Comment

Comments are closed.